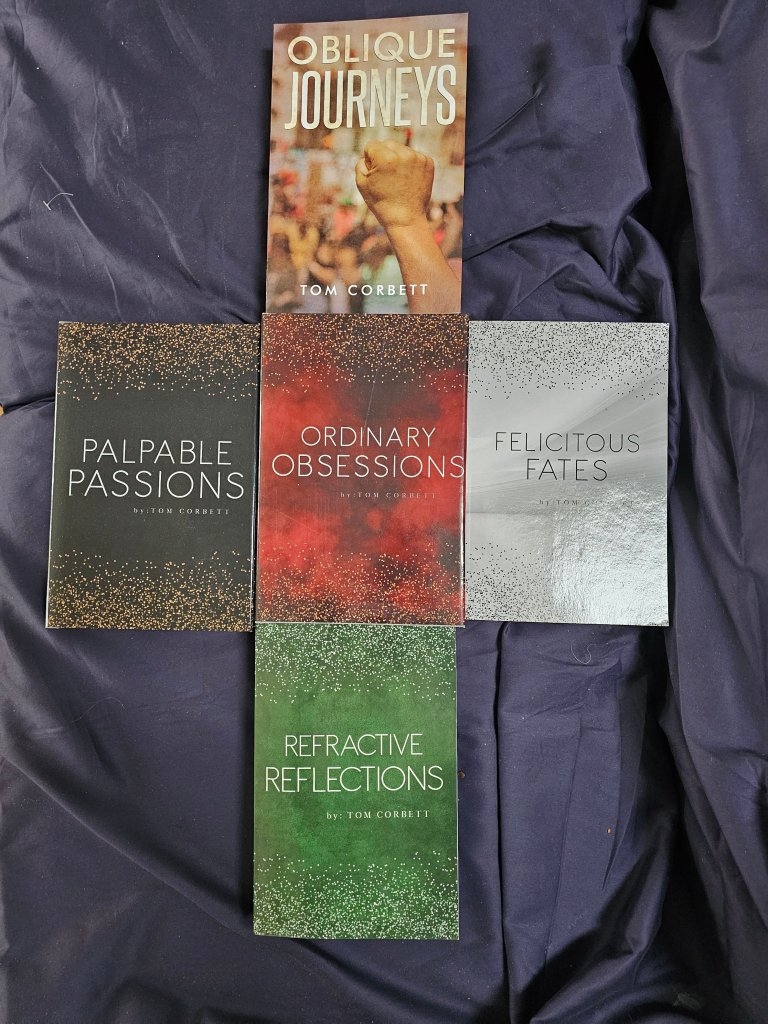

I’ve been missing from blog duty for about a week. Wow, in the beginning, I was writing a blog daily. Where did I find the time to do that? I do suppose it helps when you don’t have a real life.

No matter, I am back. Once again, I had hinted that I was past reflecting on my early years only to disappoint everyone with yet more memories on things of absolutely no interest to others. 🙃 Perhaps those who assert that I’m self-absorbed are spot-on. Still, I cannot finally move on before touching on my ill-considered effort to achieve sainthood.

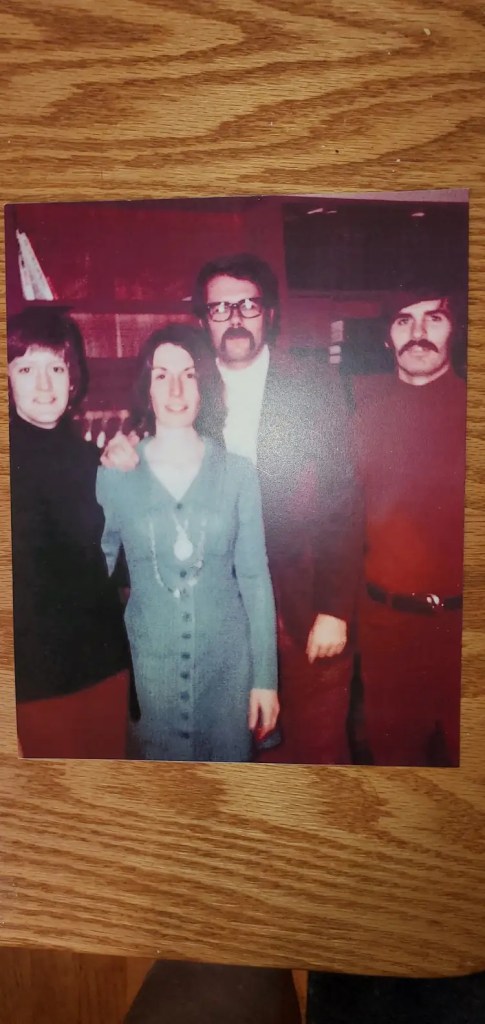

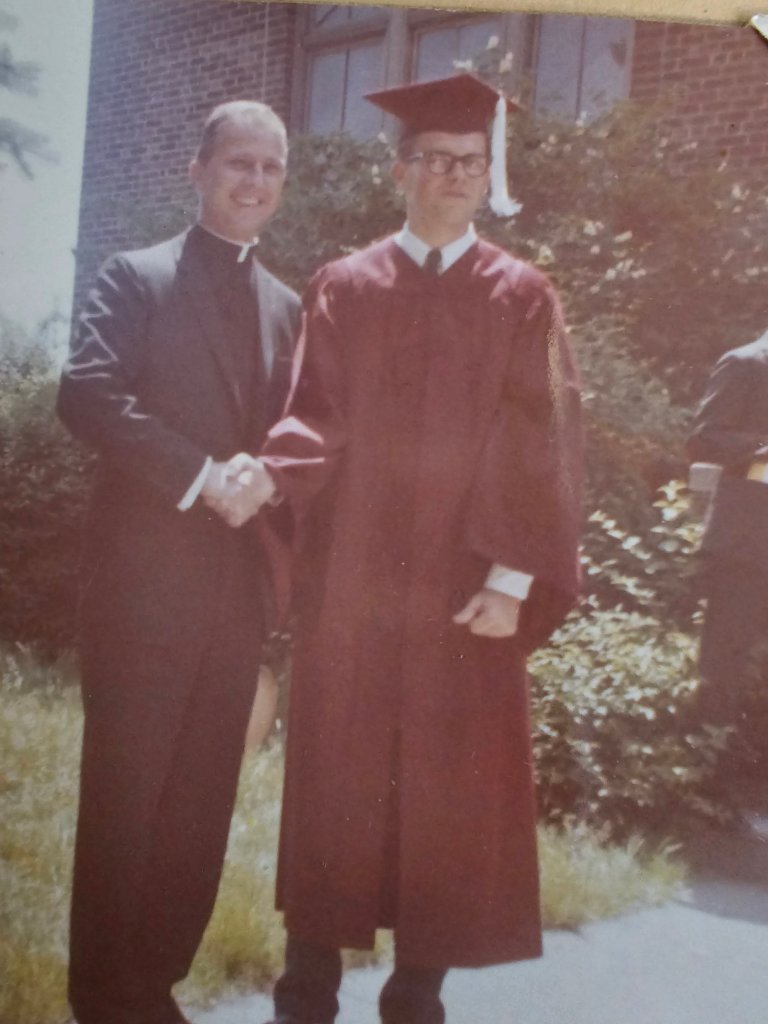

Above, I am shaking hands with Father Beck, a Catholic priest who essentially recruited young men for the Maryknoll missionary society, an order dedicated to (in turn) recruiting souls living in foreign lands to the Catholic church. That may seem to be an unlikely path for a future left-wingish Rebel. However, that’s not at all the case. Idealists are idealists. Sometimes, it merely takes some time to figure out what you are being idealistic about.

As you know, I grew up in an ordinary ethnic, Catholic, working class family. I don’t recall either of my parents ever attending mass or displaying any form of formal belief structure. However, they did pack me off to Catechism class so that I might be indoctrinated into the one, true, and universal church (or so we were told by those instructing us).

The more I think on it, they must have dragged me to church in my younger years, though I have no recollection of that. I do recall loving the serenity found in empty churches (before they were filled with noisy people). I was attracted to the smell of incense, to the candles flickering at the sides where devotees made offerings to special causes, and to the mystery of the Mass. Back then, the celebration was in Latin and some of the sermons were in the language of the dominant ethnic group for that church … Polish or Lithuanian.

I cannot say I was drawn to the church in any particular way as a kid. All my friends were Catholic. It was merely part of the background noise of my life. I resisted going to one of the Catholic elementary schools I’m the early days. There were a slew of them back then, a holdover from the times when the Church maintained separate institutional systems (schools and hospitals) to avoid mingling with Protestants whom we knew were going to Hell. All the Catholic elementary schools were taught by nuns who had a hellish reputation.

High school was different. I wanted to go to Saint John’s Prep … the best religious school in central Massachusetts taught by the Xaverian brothers. This was the place to go for kids from my tribe. There, I would be indoctrinated into the basics of the faith along with a rigorous curriculum that prepared us all for college. It was a no-nonsense place where discipline was rigorously enforced and academic excellence prized. Hell, the teaching brothers had no life other than beating some knowledge (and good behaviors) into us. The beatings occasionally were literal.

As I have written earlier, I developed a keen sense of purpose during these years. I became increasingly sensitive to the injustices around me, especially regarding civil rights and matters of equality of opportunity. It seemed built into my DNA. I won’t dwell on that awakening since I’ve discussed it elsewhere. Suffice it to say that I started looking about for a place to satisfy my growing attachment to a purposeful life.

Enter thoughts of the Priesthood. I cannot recall when this became real for me. I do recall attending daily Mass in my senior year of high school. Yet, there were doubts even then. I would sit in religion class arguing (only in my own head) against some of the Catholic teachings in which we were being indoctrinated. But I pushed those doubts aside. That proved to be an error, as I would discover soon enough.

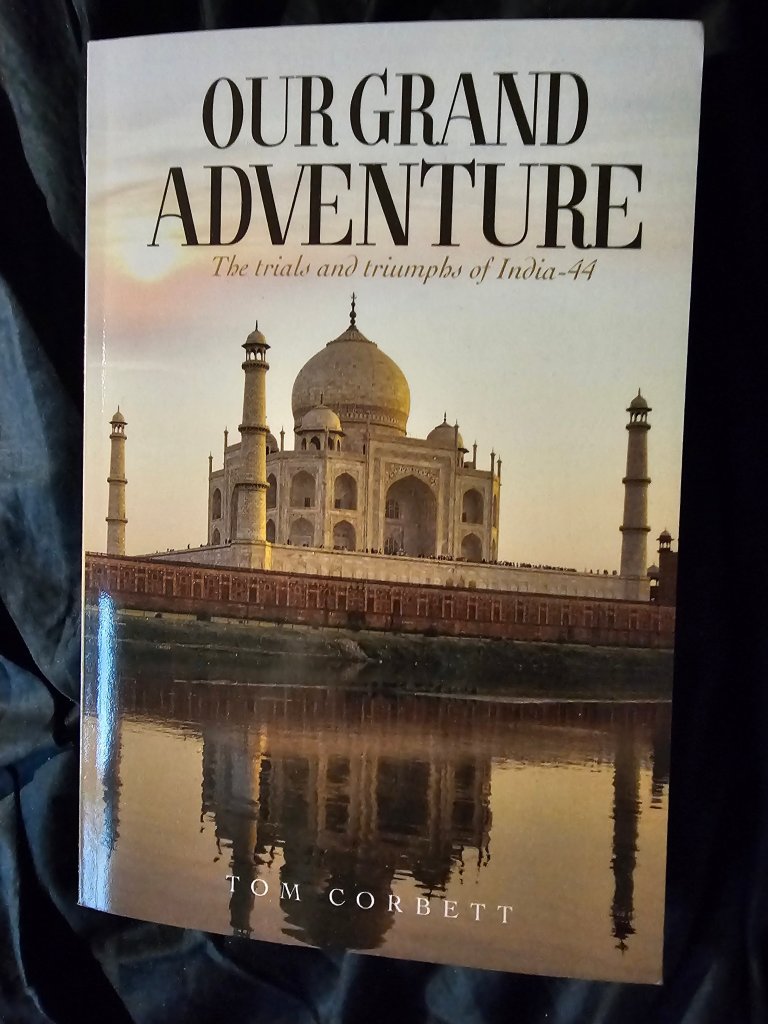

So, in the Spring of 1962, I visited the Major Maryknoll Seminary in Ossining New York … a lovely site overlooking the Hudson River as I recall. That hooked me. In late August of 1962, I got on a bus and headed for Glen Ellyn Illinois (outside of Chicago) to the order’s minor or college level seminary.

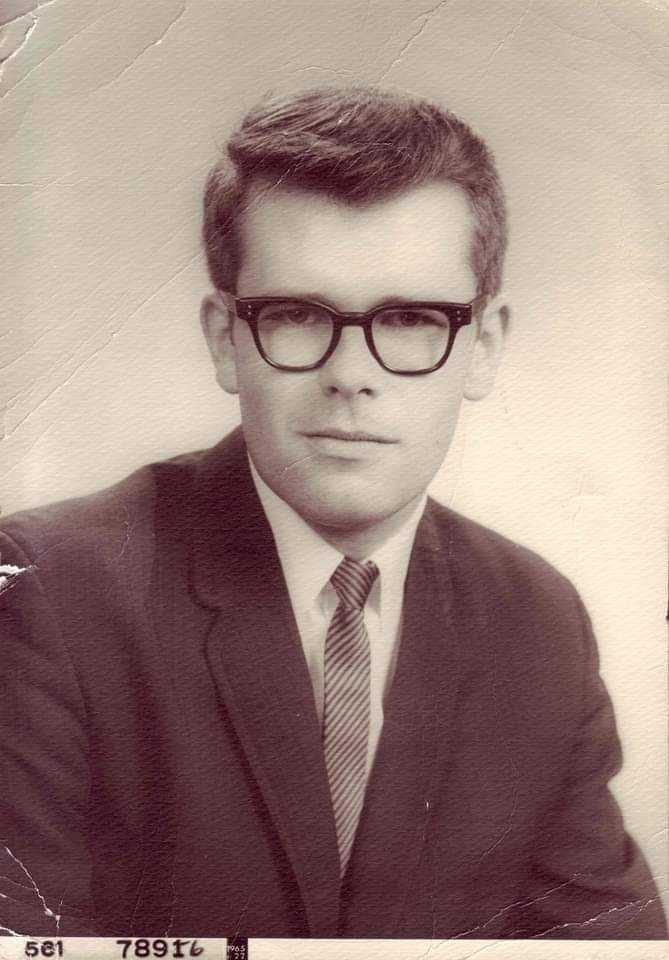

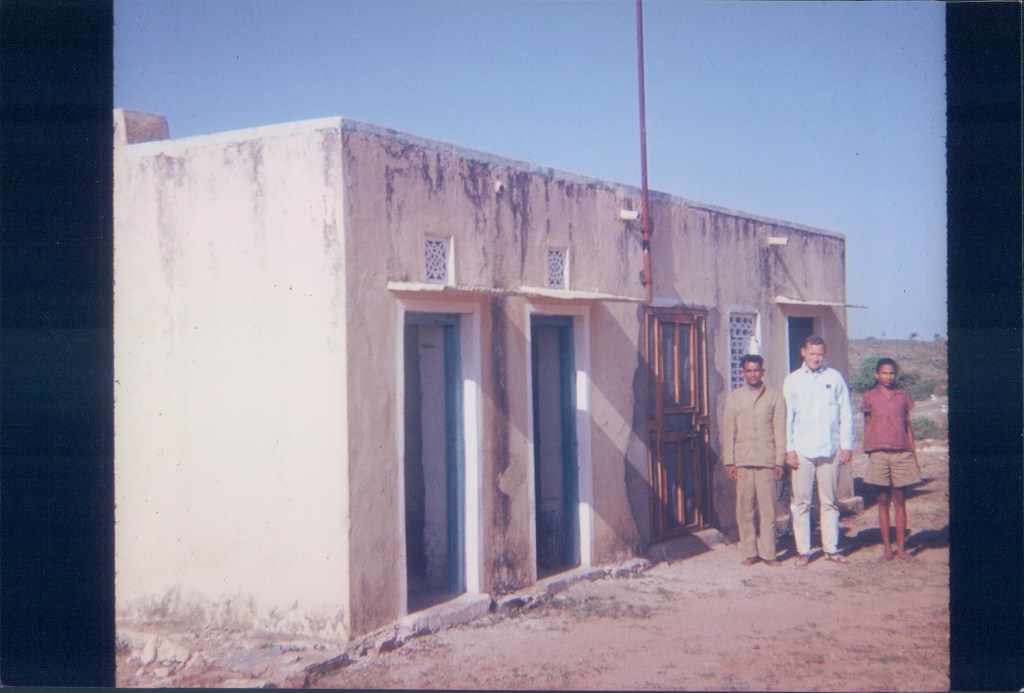

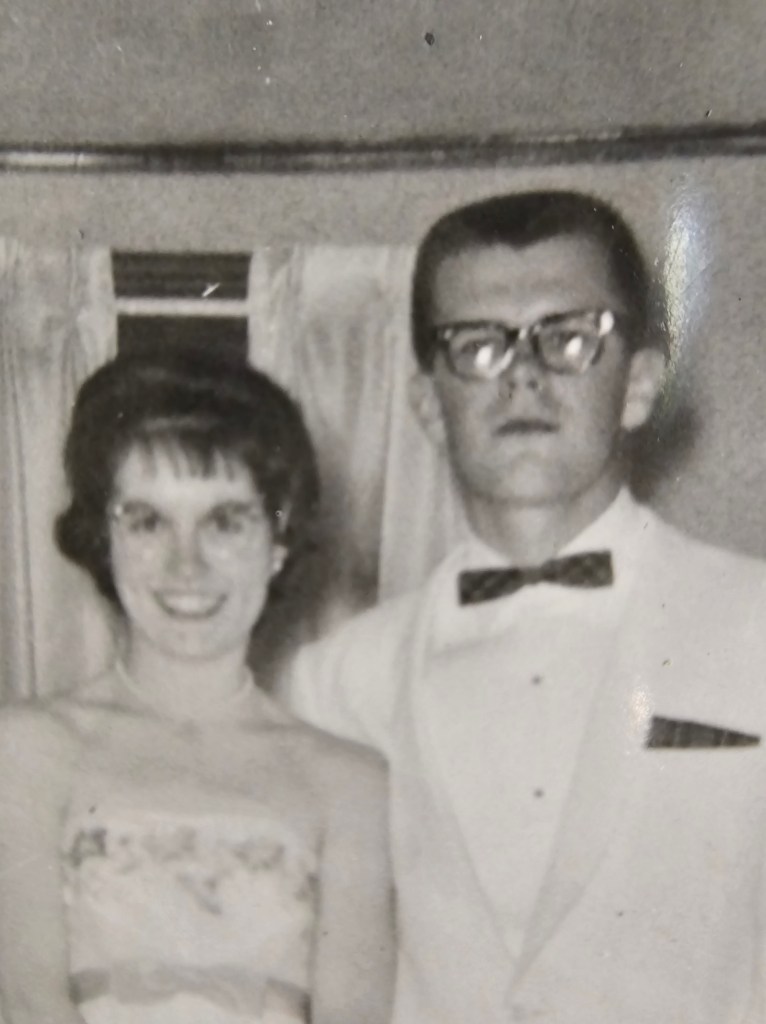

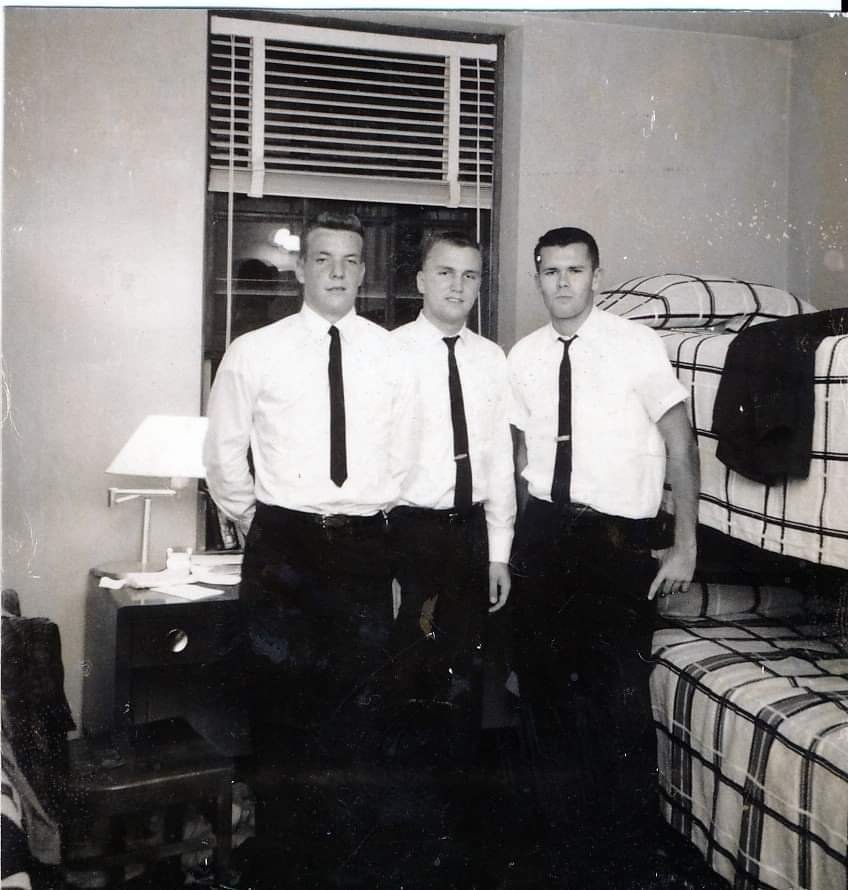

Here I am (on the right) with my freshmen roomatesĺ. My God, was I ever that innocent? I suppose a seminary is a bit like a military academy. Each day is highly structured. You go from a wake up alarm at 5:30 or so through religious services, classes, mandated work assignments, physical training, more indoctrination, and then more studies. There were long periods of enforced silence and few opportunities to leave the campus.

In many ways I liked it. My fellow seminarians were nice. I did well in my studies. There were places on campus where I could walk and think about things. It was all encompassing and became comfortable. The thought that it would take 8 years to become a missionary priest was a bit daunting but so be it.

We were not saints. We broke the silence rules, played tricks on one another, and worked out our frustrations in vigorous athletic competitions. I can yet recall pitching an entire basball game for the first time in many a year. I could barely move the next day.

There were some special moments. I can recall the Easter celebration in the circular chapel. We all filed into a darkened chamber at midnight. Each of us had a candle, each of which was lit one after another. In the glow we repeated the phrase ‘he is risen’ again and again. Goosebumps return at the memory.

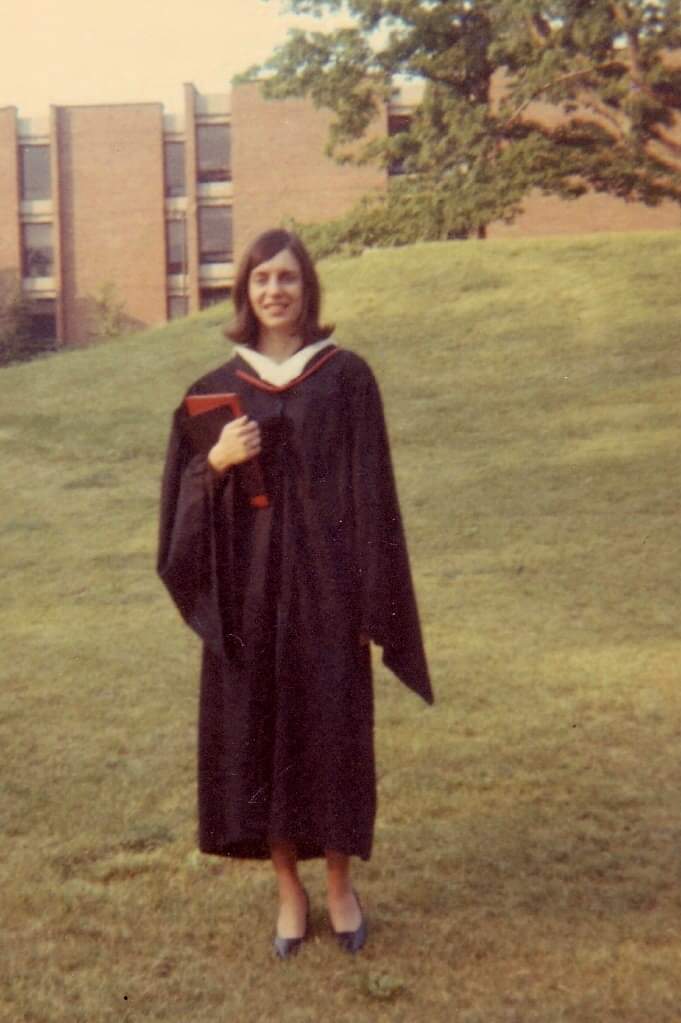

In the pic above, I am with my second year roomates. By this time, doubts I could not ignore were creeping in. The internal arguments I suppressed in high school religion class kept returning and with greater force. Yes, I wanted to do good. Yes, I wanted to find purpose in life. Yes, I was searching for meaning. But no, when I looked deep inside, I did not believe in a God deeply enough to support a vocation. I was way too rational.

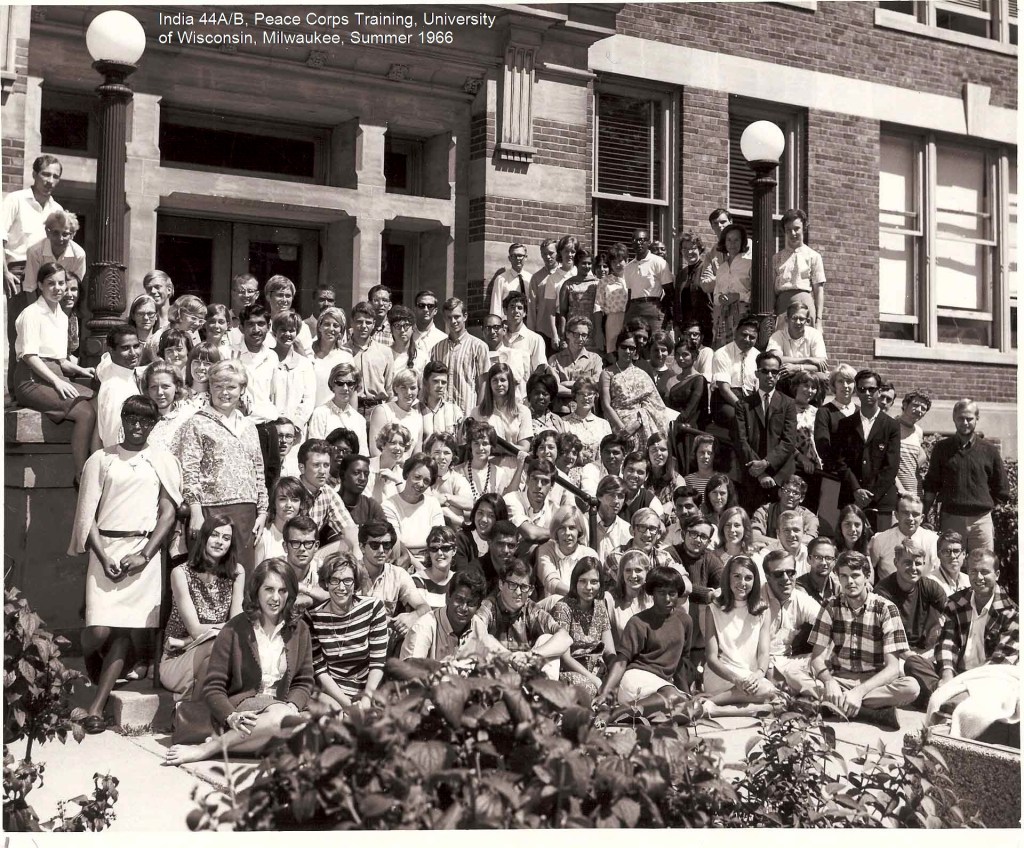

You can recall the rest. I realized one day that I had been fooling myself. It was time to face reality. I left, returned home, enrolled at a secular college, and shed any remaining religious beliefs. Rather than resolving my search for purpose through the salvation of souls, I would find alternative ways of finding meaning in life. That search started with trying to stop an ill conceived war (in my estimation) and continued in a life working on critical social issues.

And that really is the bottom line. My Seminary experience was never a failure. It was merely a temporary detour in the search for what I was meant to do. In the end, it was a good thing. You seldom make real mistakes. Rather, you stumble upon learning opportunities all the time, but only if you recognize them as such. Just make sure you see them as gifts … not errors.