This is 1944, probably in the Fall given how we are all dressed. I am the little shit squeezed between my father, Jeremiah Thomas Corbett, and my mother, Jane Ann (Spiglanin) Corbett. It was considered a mixed marriage in those days … the joining together of members from the Polish and Irish tribes in Worcester Mass. They probably still liked each other in these early days, their youth and hopes had yet to be dashed by a harsh reality and lost dreams. That would come later, as did the bitterness.

I cannot imagine that my presence in their lives was anything else than a serious inconvenience. They were players in their youth, lovers of gambling and night-clubs, and of drinking with friends. I would be pawned off on my grandmother who lived in the 3rd floor tenement while we occupied the first floor flat of the ubiquitous three story residential buildings that populated Worcester Mass. I liked my grandmother. She was straight out of central casting, plump and gey haired and matronly. Besides, she made the best eggnoggs imaginable.

I was also schlepped to the nearby tenements of two aunts who would be stuck taking care of yours truly. Such a joy I was 😊. In any case, I would be amused later in life by the arguments in the family about who really raised me … my mother’s sister or my dad’s sister. It was inconceivable to me that rational adults wanted to take credit for such a questionable accomplishment 😅. But there you have it.

When no one could be persuaded to look after me, I do recall being taken (reluctantly) to the homes or apartments of friends where my folks and their friends would gather for evenings of good cheer and poker. The drinks would flow among the adults, the laughter was abundant, yet I never had trouble falling asleep among the coats that had been piled on a spare bed. To this day, I can nap amidst total chaos. Napping is my personal strength.

One image survives from my earliest memories. Each morning, I would find mom sitting in her robe while smoking a cigarette and drinking a beer as she argued with one of her sisters on the phone. (Note: she mostly worked evenings serving drinks in taverns and night clubs.) She loved her siblings, but they fought like cats and dogs. I cannot imagine my mother denying herself cigarettes and beer during her pregnancy with me, even if the dangers were known in the early 1940s. How I was not born severely damaged is a mystery. Then again, perhaps I was … which would explain a lot about how I turned out.

Mostly, like all children of that era, I was left to my own devices. I would be thrown out of the house early and told not to return until the streetlights came on. If it rained, my mother had a favorite song … rain, rain, go away, Tommy wants to go out and play. This meant that she hoped the rain would stop so she could once again cast me out onto the streets. There, I could maraud throughout the byways and parks of Vernon Hill with a bunch of other mischievous rascals. A few years later, after I took up golf with a few ancient clubs given to me by an uncle, I would walk miles to the nearest golf club. There, I would whack the ball around the course all day (it cost one buck) before hiking all the way home before the sun set. Had I been kidnapped, the miscreants would have been in Canada well before anyone knew I was missing. Apparently, not even the perverts and pedophiles wanted me 🙄. And so, for better or worse, I was spared.

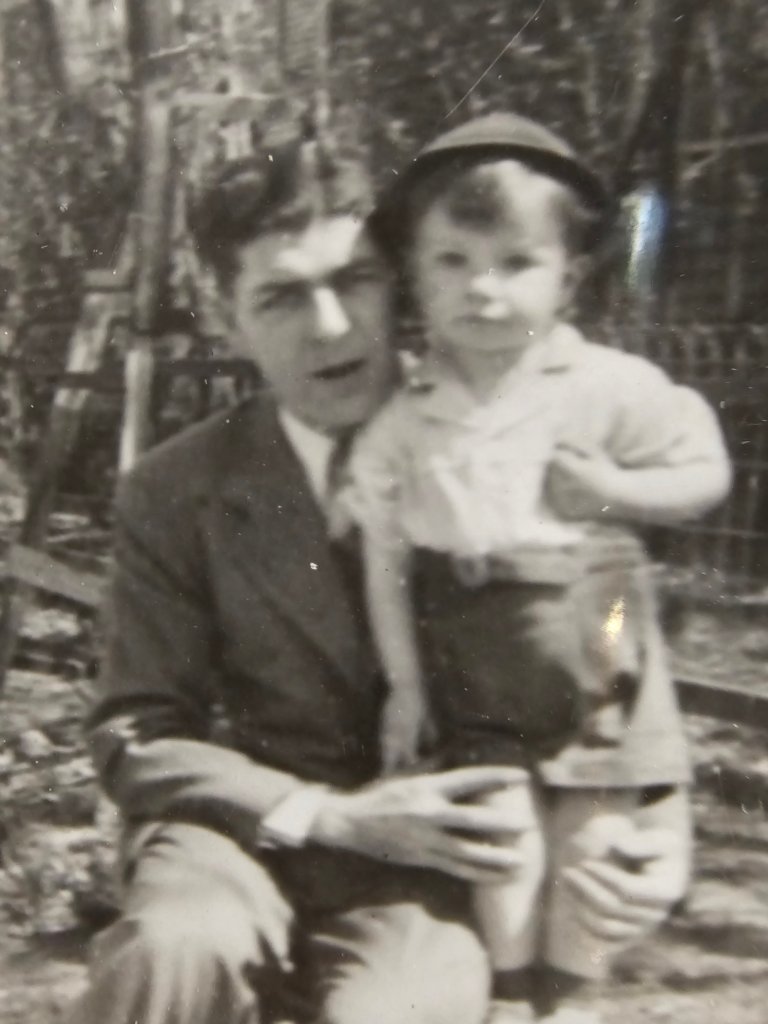

Here I am with my dad. The year is probably 1947 or 1948. He almost looks happy to be with me, actually appearing as if fatherhood was a good thing in his life. But that is not my early, though surely questionable, memory. No, my emotional sense is that I was little more than an inconvenience to him in the early years. He was fastidious while I presented him with so many messy demands and challenges. Later, that would change, but not for a number of years.

As a young man, he was a bon vivant. He had worked in the bingo circuit when it was a legal form of gambling and big business. He was handsome and likely a draw for the young ladies. He also skirted on the shady sides of life. Among his more risky ventures was an illegal football pool run by a partner and he. One day (as I was told by several sources) a local sportscaster correctly selected all the winners for that weekend’s chosen college games. That skewed the betting. He and his partner didn’t have the money that was owed to all the winners. After his tribe (the Irish) wouldn’t help, dad went to the Italians. That was the end of his semi-gangster career.

By the time I really got to know him, he was doing factory work. I’ve always wondered why he gave up on his exciting, youthful life. Did I have something to do with that? Oh, the guilt. In any case, over time their marriage was one of faded dreams and mutual recriminations. There was little love in the household.

Gradually, though, I sensed my dad spent more time focusing on me, certainly by the time I played Little League ball. When I matriculated at St. John’s Prep, a rather elite Catholic school, he became active in the school’s men’s association. He eventually became president of the Pioneer Club (as it was known) even though he was blue collared worker while many of the other dad’s were white-collar professionals with college educations.

I suspect I disappointed my dad in many ways. He was a good amateur artist. He tried to encourage me in that direction, but it never took. He had hoped I might excel athletically, but I did nothing in that arena after entering high school. He never said anything, but I had this ominous sense that I failed him time and again. That feeling of shame never disappeared.

Eventually, though, he responded to me being in his life, taking some pride in my ability to avoid juvenile detention, expecially as I began to excel academically, though I was a late and unexpected bloomer in that regard. Eventually, though, his son who was best marked by many failures and shortcomings early on, began to look as if he might excel in life. It was a matter of pride and satisfaction to dad that his one and only offspring eventually got a Ph.D. and earned a position at a top research university. I think, in a way, I achieved goals well beyond his own reach … at least in his own mind.

As I think about him, it strikes me that he was likely a brilliant man, perhaps lacking in confidence and held down by circumstances. No matter, I absorbed a lot from him … his cynical, yet dry, wit along with his story-telling ability above all. I thank him for those gifts. They helped me survive adulthood with remarkably few real talents and skills. Do, thanks dad.