I typically question myself when tempted to issue a ‘sky is falling‘ prophecy. Then again, hyperbole is the very essence of our national political discourse. Prior speculation on imminent ‘end days‘ often results in poor reviews, if not embarrassment, for the erstwhile prophet. How many times have we heard the claim that ‘this is the most important election in history?’ And yet, history continues on as if nothing of important took place.

Perhaps this is a mere reflection of my advanced years. However, the sense of doom floating around these days feels all too real to me. Yes, things were awful globally in 1944 when I was born. But the horrific evils of Fascism were on their last legs. The long terror of the Cold War had its cliff-hanging moments of doom (remember the Cuban Missile crisis), but rational minds always prevailed in the end. Really, who besides the war hawks believed in the domino theory (if Nam fell, then California was next). Besides, it was always clear to me (at least) that the Soviets would never conquer us, though we mutually were capable of obliterating society. Besides, it became clear early on that Communism would self-implode. And Islamic-terrorism? While 911 was jarring, it never could threaten our basic institutions. Just the opposite. The Jihadists, at best, would be irritants.

Now, things really do seem different … qualitatively different. I keep asking myself … why? My most common answer is that this threat to the nation is internal. It comes from within and, with this last election, perhaps reflects the normative sentiments of close to half of all Americans. They appear willing to abandon our democratic foundations. Worse, internal dissension is the most dangerous by far. Our Civil War had as many casualties as all our major foreign conflicts combined.

Putting Trump and his MAGA minions back in office suggests a fundamentally radical reorientation of the American political narrative. While the American experiment has been far from perfect, progress toward a true democracy prevailed during our 250 or so years of existence. Now, however, we are on the precipice of a radical reversal. Some form of authoritarianism appears to have been chosen over democracy, divisiveness over inclusion, power over the rule of law, raw competitiveness over compassion, money over equality, unsubstantiated belief over science and data, slavish devotion over merit and competence. And propoganda over expert analysis. To all appearances, we seem on the verge of a classic form of Fascism at home and an outdated shift to isolation globally even as the world moves toward greater integration. Trade wars and the disintegration of NATO? This is what a greater America promises? Really!

While I’m no Nostradamus, let us assume for a moment that my doomsday speculation has merit. What will our intermediate future look like? Stay with me for a bit while I lay out several distinct, but not mutually exclusive, paths … Authoritarianism, Kakistocracy, kleptocracy, and Theocracy.

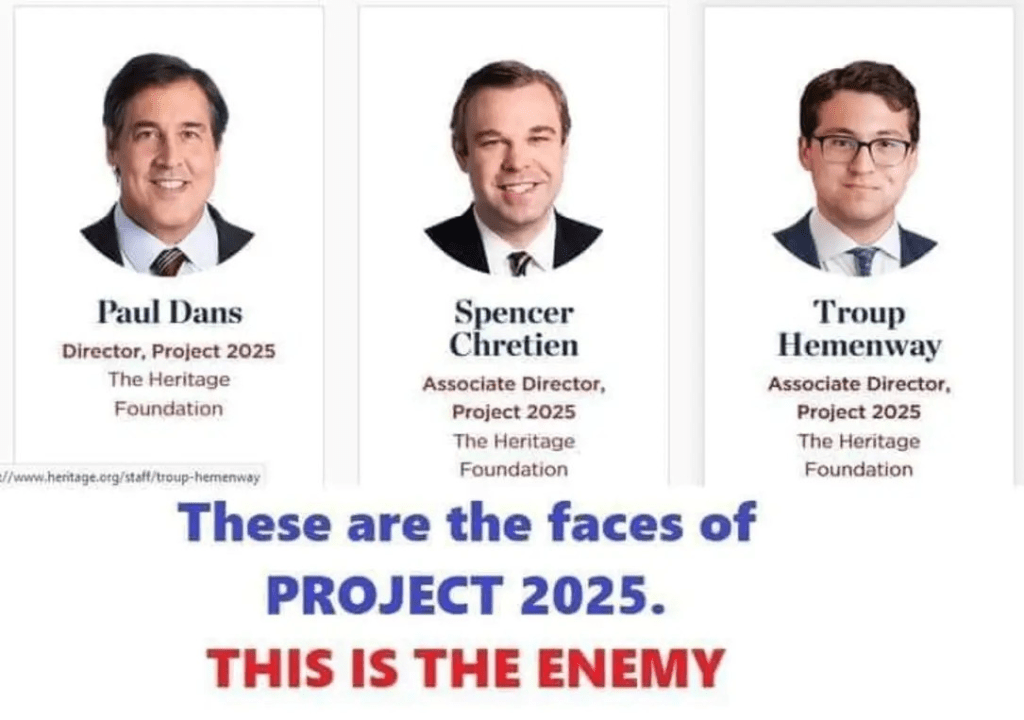

In many ways, the Project 2025 plan is a blueprint for some kind of hierarchical pattern of leadership. It contains many elements, including savaging virtually all programs designed for the common good. But I am struck by how much damage it promises to do to the checks and balances of our system of government. If there was one dominant obsession among our founding fathers, it was a fear of an excessive centralized government. They tried to balance the needs for national action against the threat of overweening power at the center. Those taking control in two weeks intend to push the limits of a centralized authority, but exactly how. Let’s briefly touch on the threads listed above.

Authoritarianism … if you have dreams of revolution, democracy is the weakest avenue to success. The French Revolution quickly segued from noble sounding sentiments of equality and liberty to the guillotine premised on lawless terror. The early Leninist Communists abandoned worker councils (or Soviets) in favor of a dictatorship of the proletariat. Revolutionaries realize quickly that the masses are difficult to steer in any direction. Rather, the architects of fundamental change are seduced by the power inherent in authoritarianism, or virtual dictatorial rule. It just seems easier and more efficient.

The blueprint for an authoritarian government is laid out in Project 2025. While it has many threads (like savaging programs designed to serve the common good), their plan to impose a virtual dictatorship on our national government worries me the most. It proposes many changes that would shift the office of the President from a limited executive set of functions to one of rather unlimited imperial control. The intent, in the long run, is to ensure a continuity of control by so-called right-minded plutocrats.

I mention one aspect of the plan here. The blueprint calls for an evisceration of protections for federal civil service employees. Vast numbers would be moved from under the existing rules that harken back to the 1880s and the meritocratic reforms introduced by President Cleveland. In the new regime, these workers would become at-will employees. Their hiring and continuation of emoyment would utterly depend on their loyalty to the top. Merit would play little role in their service to the nation and the people. There would remain few ways for civil servants to question rules from the top.

Kakistocracy … a related form of governance is often called Kakistocracy or governing by the least competent. Why would anyone choose such a method of running national affairs. Well, it mostly is a default option. That is, when loyalty to the top managers trumps all else (pun intended), the number of competent candidates is dramatically reduced. Besides, they might think for themselves … Heaven forbid.

Think about this, Robert Kennedy Jr. as head of the Department of Health and Human Services. I worked there for a year (and consulted with staff there over many years). They deal with enormously complex policy issues that demand the highest level of knowledge and analytical skills. The staff I worked with were knowledgeable and highly professional. Kennedy’s qualifications are that he dropped off the ballot in several states, obsequiously sucked up to the Donald, and he had a brain worm in the past. His views on medicine harken back to the days of bleeding with leeches.

And take Matt Gaetz. Yes. Someone take him. Appointing this cretin as the head of DOJ was beyond the credibility pale. Fortunately, he was so bad that his appointment collapsed immediately after his record as a pedophile and drug user became public. But surely, Trump had to know when he announced his appointment. He just didn’t care. It is as if Trump sits around contemplating who is the most ridiculous candidate for each position. The worse they are, the better they look to him. And the easier it will be for him to control them.

Kleptocracy … This is a form of governance with a rather long tradition in American history. Essentially, this approach suggests that wealth is equivalent to power. Money has always played a big role in government, especially during the Gilded Age of the late 19th century and the roaring twenties of the decade preceding the great depression. There have been many attempts at redressing the oversized role of money in politics, the McCain-Feingold legislation being an important example. All failed in the end.

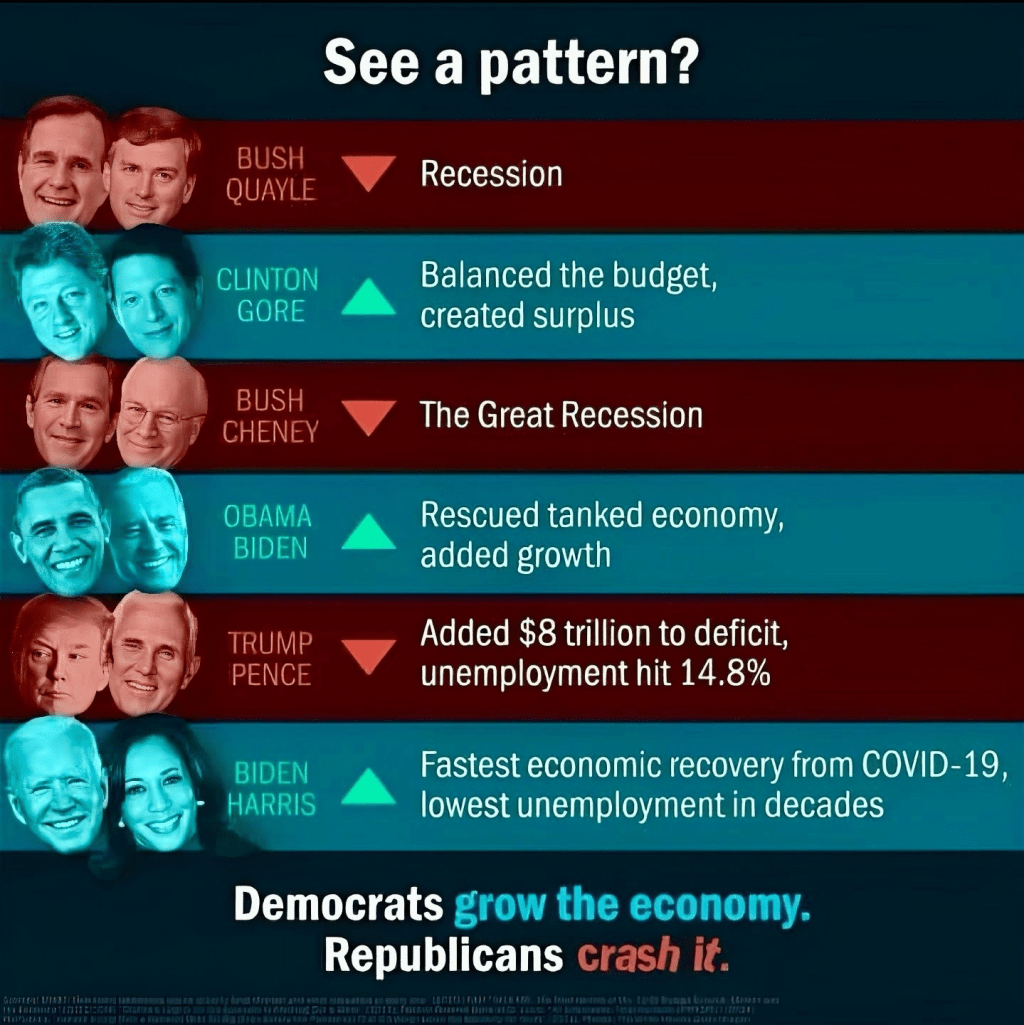

Now, it seems impossible to turn back the tide of riches dominating principles in our public life. Inequality has reached levels reminiscent of the late 1920s, or just before our most dramatic economic collapse. Such a concentration of treasure among the privileged few bequeethes enormous possibilities for increasing political control on to them. The MAGA crowd does not even bother to conceal that they are in bed with a few wealthy oligarchs. The Dems struggle to maintain some independence, but that becomes increasingly difficult as political fortunes become increasingly dependent on money.

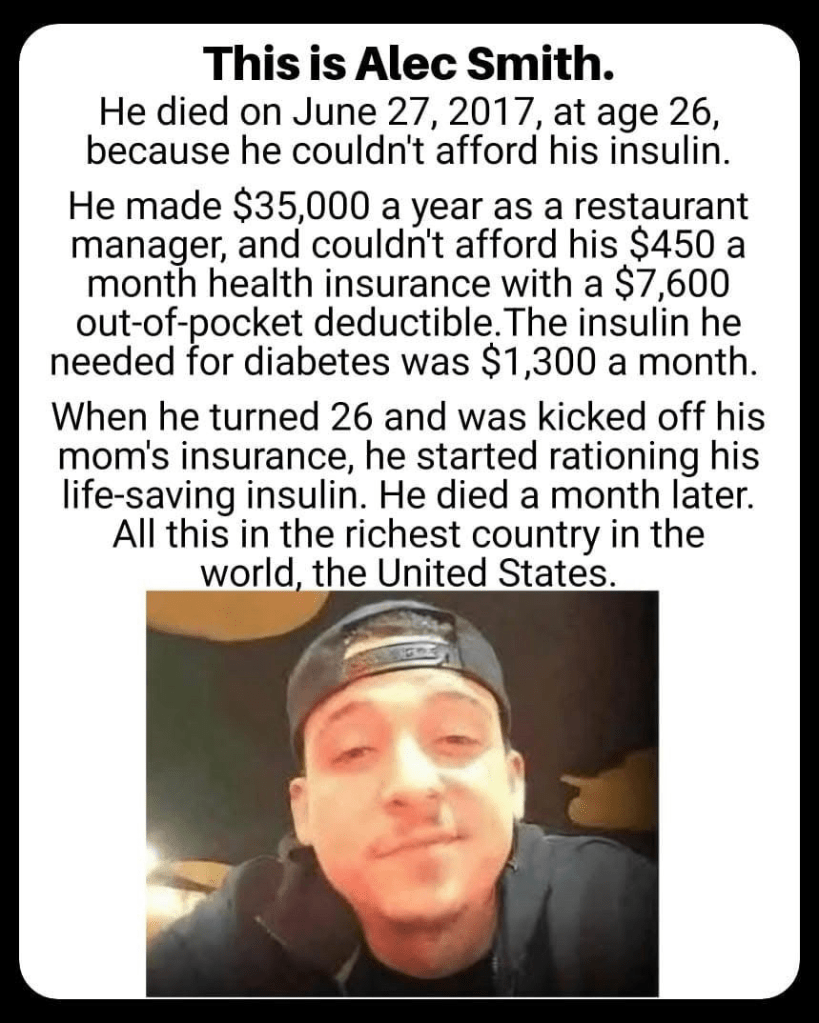

It has been widely accepted that the supply-side tilt of federal policies since Reagan has resulted in a $50 trillion dollar shift of wealth from average folk to elite. At the same time, the so called middle class has been hollowed out … falling by some 11 percentage points since 1980. It strikes me that Trump’s DOGE, the department of government efficiency, will be a transparent effort to savage outlays in most programs helping average or struggling folk. Under Musk and Ramaswamy, these program recissions will be exploited to justify new tax cuts favoring the ultra wealthy. And that is just the beginning. The bottom line is this … the next four years will witness an unabashed raid on the public treasury unlike any we have seen in history. The spiral will accelerate … more money, more power to the elite. Heaven help us.

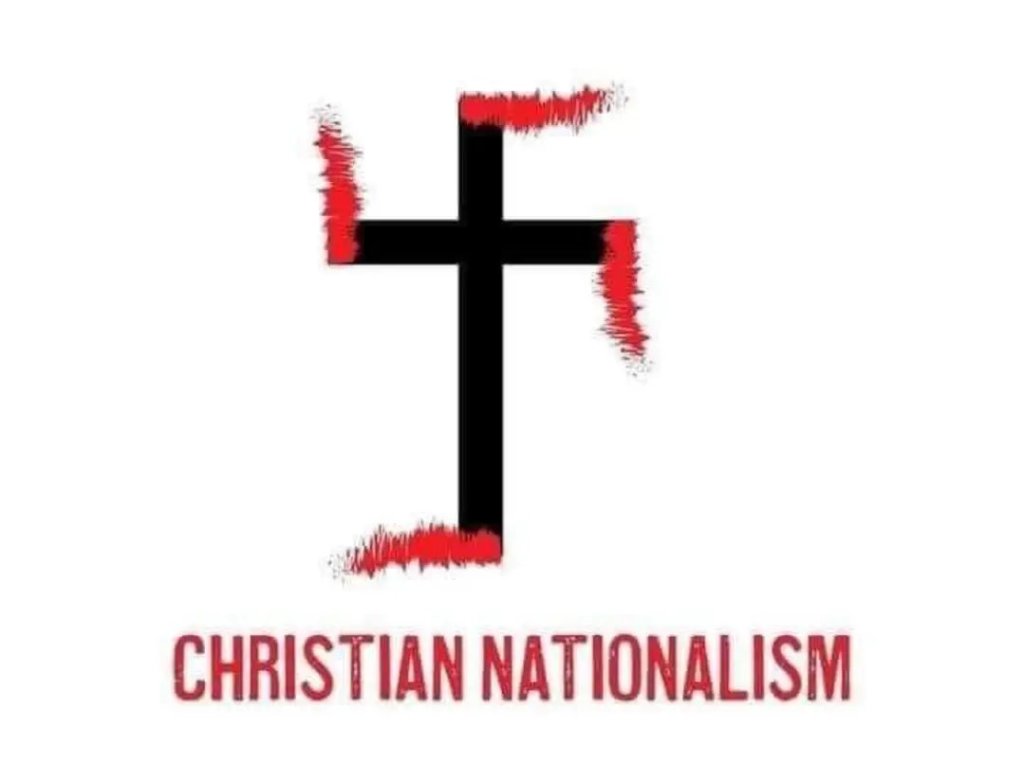

Theocracy … the final directional option for the future of our government is a well-known variant called theocracy. This is where we jettison all pretense to a secular government in favor of one based on religious beliefs and authority. If you need an example, simply look at Iran or Afghanistan. In such places, secular laws have been replaced by the Sharia where the views and pronouncements of Mullahs outweigh those of experts and elected officials. The interpretation of divine will overshadows all secular considerations.

Of course, the big question is which God and which representatives of that God will dictate divine will in public life. Obviously, the Bible as an arbiter of public policy is a very rough and inexact tool. I mean, do we really want to reimpose slavery, as endorsed in the Old Testament, or stone to death female adulterors … probably a bit harsh for contemporary tastes. I’m sure that the Evangelicals waiting for the anointing of their political hero have other, more favorable, thoughts on these matters.

In my opinion, the theocratic option has never been a serious alternative. It has been a convenient misdirection tactic to be employed by the plutocrats while redirecting vast sums up the fiscal pyramid. The ploy is simple. Confuse and distract the victims with contentious normative issues so they don’t notice the ongoing theft bankrupting them. Things like abortion, alleged attacks on Christians and (unbelievably) Christmas, and threats to Christian cultural hegemony are enough to keep the pot boiling and the sheep distracted. So far, I have not seen any evangelical luminaries ascending into real positions of authority, but the scam undoubtedly will continue, if not increase.

Which of these strategic threads will dominate? All to some degree. The kleptocratic (or oligarchic) alternative likely has the advantage (to my eyes at least). Money talks while bullshit walks, as the old saying goes. But each approach plays a role in the entire scheme of things. And so, each will be featured from time to time, depending on circumstances. For example, if the economy sours, expect a resurgence of theocratic concerns and issues.

Unfortunately, we cannot escape one disturbing reality. The man at the center of this circus is, without question, the least competent and the most damaged public figure in my lifetime. I laugh every time the MAGA minions attack the Dems for hiding Biden’s cognitive decline. Really?

It is readily apparent that the MAGA crowd engages in crass projection … assigning behaviors to their opponents that they have themselves mastered all too well. But this one is over the top. Just read the exposes written by those who closely worked with Trump in the first go around (those who were not part of his cult). They all were appalled by his cognitive and ethical shortcomings. Many spent their time trying to keep the Donald from doing even more damage. You should never cast stones if you live in a glass house.

So, wither America? I have not the slightest clue. But I do feel we face the most perilous challenges in my lifetime. Worse, we are at the mercy of an unstable narcissist driven mostly by a dark and forbidding paranoia. I haven’t prayed since my late teens, but I just may start again.