No male of my generation came of age without facing the crisis associated with the Vietnam conflict and the military draft. It was an obsession for nearly all of us, dominating our young lives as we came of age during the 1960s and early 1970s. Today’s kids, absent a compulsory military draft, cannot fully appreciate the angst we endured back in the day. Our young lives appeared to be at risk and, for too many, they were.

Yet, our existential dilemma was about more than mere survival. It imvolved a desperate and fundamental struggle to define our personal core values. For my generation, unlike more recent cohorts if survey results are to be believed, ‘formulating a personal set of beliefs‘ was a critical undertaking in those tumultuous 1960s. We sought to understand what we stood for and for what, if anything, we might be willing to perish.

Like many others born during, or immediately after World War II, I grew up embracing the United States as a beacon of hope and righteousness in a deeply divided world. From the defeat of fascism and state-militarism, totalitarian models that dominated much of Europe and the Far East by the 1930s, there emerged a bipolar world … a seemingly Communist monolith bent on world domination versus a ‘free‘ world led by the new American superpower. It seemed like a titanic struggle to the death.

As a working class Catholic kid, I had fully absorbed the cultural tenets in which I was immersed in those times. We were in the midst of the Cold War. It was a binary world to our minds. You were either on the side of God and truth or you had embraced evil. No neutral ground was permitted, no nuanced interpretation of events could be entertained. I was studying to be a priest in a Catholic Seminary when the Cuban Missile Crisis erupted. I can recall seriously considering leaving my studies to join the military, assuming I would return to my service to God when the good guys had triumphed (if I survived that is).

Within two years or so, my worldview had undergone a shattering transformation. Today, the ‘hard right‘ would argue that I had been indoctrinated after leaving the seminary and matriculating at a secular college. Yet, think as a might about those critical days, I cannot recall any professors or classroom discussions where anyone consciously attempted to shape my perspective. No, the process was way more subtle and based much more on learning to think for myself at long last.

I read widely and voraciously, absorbing all I could from history and current events. More importantly, I thought hard about what I was cognitively ingesting. Outside the classroom, I spent countless hours debating the issues of the day with other razor-sharp students. I found myself in a dizzying and exciting world of internal turmoil and self-discovery.

To my amazement, I uncovered a world that was quite nuanced, not black and white, not simply divided between evil and good. Soon, I became aware of our own domestic national sins, failings such as the system of legal apartheid that oppressed members of minority groups. I began to appreciate our own sins of commission (the overthrow of elected governments in sovereign lands that we simply didn’t like) and sins of ommission (the implicit support of heinous and murderous regimes simply because they supported our point of view).

Still, shedding one’s embedded cultural skin is not easy. In fact, it was torture and replete with self- doubt. I’ve recounted my final break on supporting our Vietnam adventure elsewhere. The final rupture came in a day long debate with a fellow student who, like me, had been awarded a summer undergraduate federal research grant. We spent a full day avoiding our work while hammering away at each other’s position. In the end, I realized he was right and I was wrong, though my process of change was well along by then. Soon, I was the leader of the liberal-left group on campus.

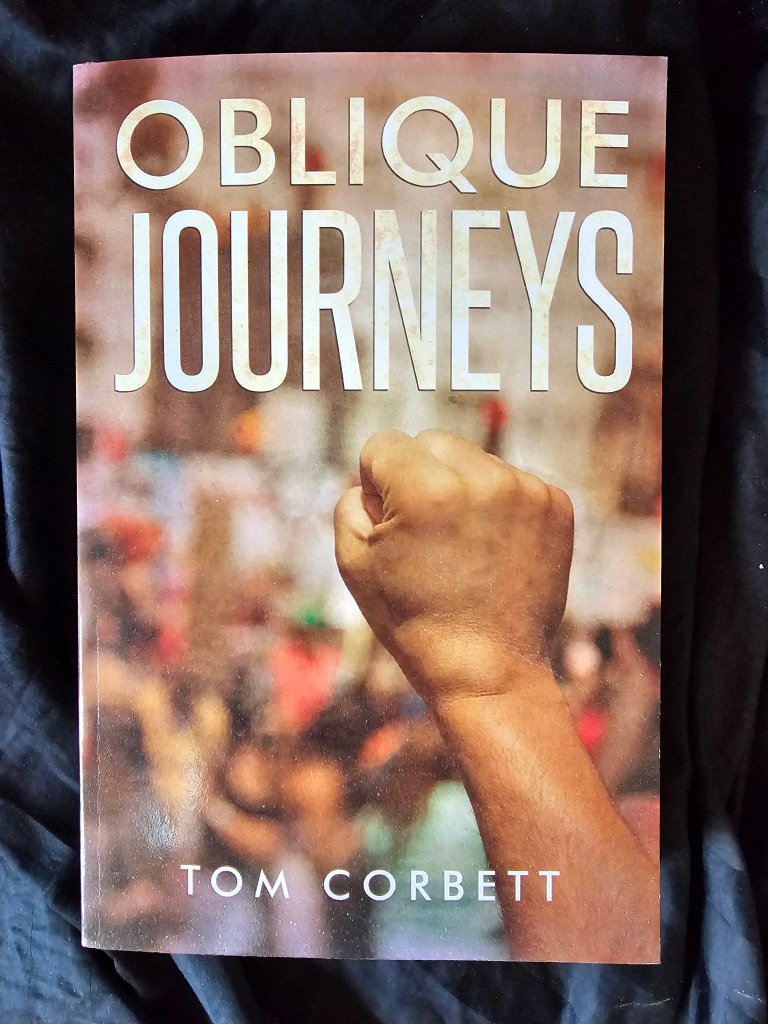

I cannot fully recount the character of the debate back then here. It would take a book, like the one I posted above, Oblique Journeys. Our best and brightest leaders, to my mind at least, made simple-minded errors like conflating the legitimate desire of the Vietnamese for independence with a presumed ideological attachment to the Soviet Bloc. The very notion of a monolithic block was already cracking apart if one were to look closely even then. In retrospect, nothing was more patently ridiculous than the domino theory employed to justify the killing of millions of Asians (if you include the Cambodian killing fields) and some 57,000 Americans. If the Vietnamese were to finally achieve independence after decades of fighting the Japanese, the French, and then the Americans, they were not likely to invade California. Thinking about their struggle objectively, they made our Revolutionary war (analogous to that of a small would-be nation taking on the world’s formost superpower) look like a walk in the park. And how did things turn out? Hell, Americans are now retiring to Vietnam because they like the weather, the people, the cost of living, and the food.

Yet, what does one do when one’s conscience demands that you refrain from participation in a conflict you feel is unjustified, perhaps evil, but are faced with a legal mandate to fight and kill? How far does one go in the name of principle? What price is one prepared to pay? That was the critical question that dominated my life over the next several years. It was a struggle that plagued many of my peers.

The goal for guys like me was to make it to age 26 without being drafted. As it turned out, I came very close to being swept up in the military net during my final year of eligibility. As the months slowly ticked by, I entertained many options. I consulted with lawyers, considered conscientious-objector status, and looked to Canada as an escape. Finally, simply refusing to participate, accepting jail as the necessary price for having humane values and a nimble mind, remained an option. Perhaps it was the most honest option. Such things swirled about me. Just what would I do if ultimately pressed to the limit?

In the end, I made it to my 26th birthday though it was a close-run thing. I did have to take my draft physical in Milwaukee. It proved a hilarious exercise. There was a question somewhere in the process that asked if you had ever been a member of an organization that advocated the overthrow of the U.S. government. I raised my hand and asked if S.D.S. (a leftist group that became radical after I dropped out) counted. The Seargant replied ‘you bet your ass it does, buddy.’ So,I answered yes. At the end, when everyone else was permitted to leave, I was marched to another floor to be grilled by 3 members of military intelligence. That experience did afford me a few moments of humor in an otherwise sobering experience. They would ask … will you fight any and all enemies of the United States? I would gaze at the ceiling as if thinking hard on the question before responding with … I think we need to define ‘enemy.’

Nothing sharpens your philosophical core like facing adversity. And we all made our own decisions in the end. I recall having drinks with a fellow student in grad school during these trying times. He had been in ROTC (and on the football team) at Boston College. Upon graduation, he was off to Nam as a 2nd Lieutenant. He hit the ground wanting to ‘get those Commies.’ Within weeks, he understood the folly of his predicament and of the war more generally. Now, he simply wanted to get his men out alive. His agony ended when he was shot up on patrol wounds that left him with a pronounced limp. He had become a more virulent pacifist than I was.

In Oblique Journeys, I take some of my personal experiences and challenges and turn them into a fictional story of what might have been. Writing a frictional novel based a number of actual personal experiences and on my take of the issues of the day gave me a great way to talk through that critical period of my young life. At the end of the day, such dramatic choices push us, perhaps even make us better. But I wouldn’t wish it on anyone.

One response to “What might have been … continuing further!”

Well done.

LikeLiked by 1 person