In the previous blog, I explored the zeitgeist of that era in which the Peace Corps volunteer experiment emerged. Freed from pressing economic want, and spurred on by a lessening of both financial insecurity and inequality, the youth of America (a reasonable number at least) turned their minds and hearts to nobler aspirations. With that peculiar and illusory optimism only found in the young, they (we) believed an even better world was possible.

After all our training and preparation, I can still recall my first moments in Delhi. The July heat was like a blast furnace. But we were able to ignore that momentarily in light of our recent brush with death. The cowling of one engine fell off our Air India flight as we entered Indian airspace. This unsettling incident warranted a news article in the next day’s Times of India. What we were less able to ignore were the cacaphony of sights and sounds that assaulted us. You can be told over and over what to expect. Reality, however, is always much more real.

We spent a few more weeks trying to become farming experts. My group (India 44-B) was initially trained to be poultry experts. Then, half way through, we were switched to agriculture. That should have been clue number one that the planning for our exciting adventure might have been a tiny bit flawed. Despite the rather obvious confusion at the top, our training staff was superb. The preparation we received was intense, innovative, and remarkably immersive. In the end, we all learned an extraordinary amount about who we were and what we might accomplish in our service and, more importantly, beyond. I think, all things considered, we experienced far more change than anything we effected in India or the sites in which we were placed.

Some 50 years after the formation of the Peace Corps, there was an anniversary celebration in Washington. The Indian Embassy had an event for all former PC volunteers in town. The top Embassy official noted that the PC contribution to India (which came to an end in the mid 1970s) was less in terms of any technical improvements and much more in terms of cultural connections. We learned from our hosts, and they learned from us. Despite our shortcomings and mistakes, we showed Anericans and America in a better light. Well, that’s my story, and I’m sticking with it.

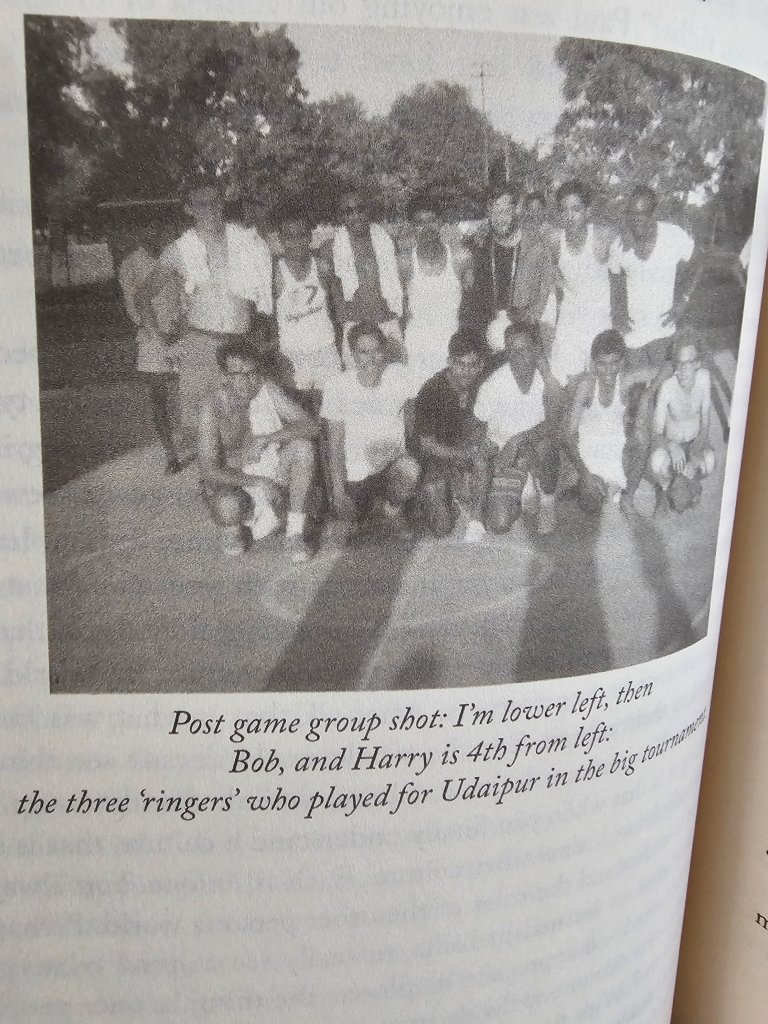

For example, before heading off to our villages, we played several games against a team from the local Udaipur college. (See pic below). Arguably, we held up the honor of American round ball before enthusiastic local crowds until they brought in some ringers from a military unit. On that day, we lost big time, both on the scoreboard and in the physical punishment we endured. The locals were delighted at our being thrashed, but we all ended on good terms. In fact, the local ball players invited me (along with two others from my group) to join the Udaipur team to compete in the all-India tournament to be held in Jaipur. The local team erroneously concluded that adding the hot shot Americans would improve their tournament chances. Alas, not to be. Soon enough, we found out that the rest of India could play the game at a high level (we were out quickly). But we all had a great time.

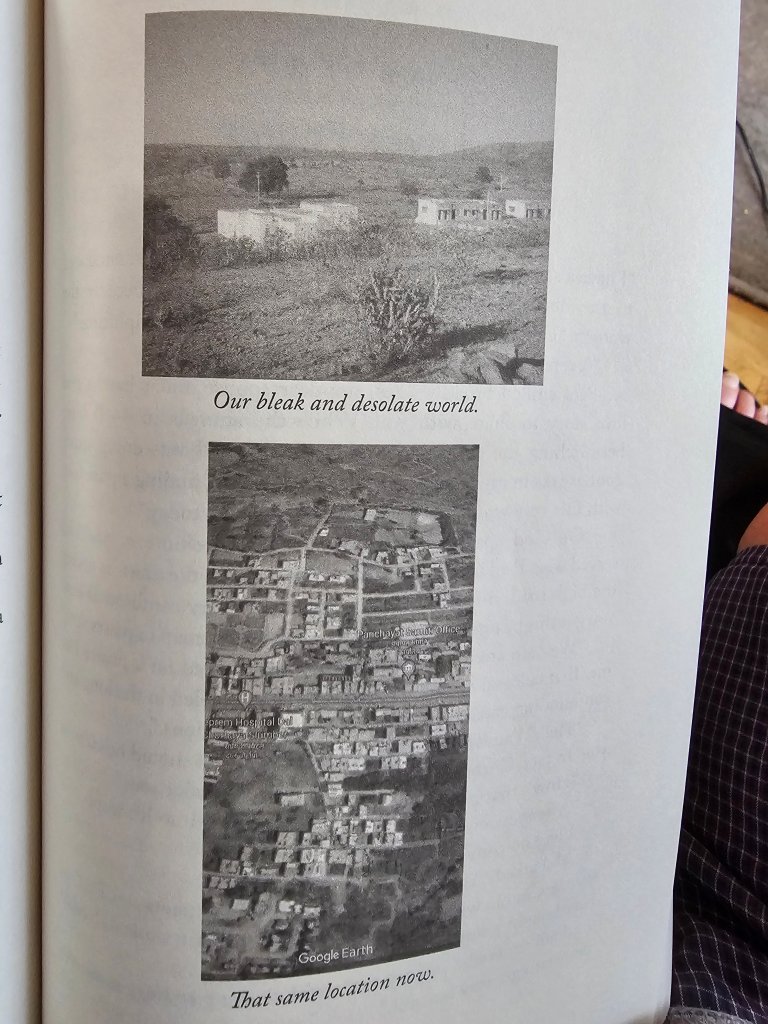

I can’t relate the actual Peace Corps experience in a blog or two. Only a few impressions can be touched upon (or you can get a copy of Our Grand Adventure). In the pic below, you can get a feel for our situation in the field. I was stationed about 45 to 50 miles south of Udaipur in what can only be described as a desert wasteland. I lived in government housing attached to the local Panchayat Samiti (government development office). All the other officials chose to live in town, for reasons obvious to me. I never had running water, electricity was only installed after 6 months of promises, and I crapped in a hole located in a room attached to my humble abode.

The experience was challenging in many ways. We all were struck with a variety of physical ailments … some in my group became very I’ll (either hospitalized or medically discharged). I had giardia, ringworm, and lost so much weight that my mother (seeing pictures of me) was tempted to call our Congressperson to have me rescued. But health wise, I escaped relatively unharmed, encountering relatively few bouts of dysentery and no serious ailments. I did live in fear of the dreaded guinea worm. These started out as cysts to be ingested from local well water which grew into long worms that eventually would pop out of an arm or leg. All these years later, I still have nightmares.

The real challenges were the isolation, the loneliness, the heat, and the demands associated with an inscrutable culture. There was no way to negotiate the complexity of the social rules there without error. At the least, one had to consciously think about what to say and how to behave when in public. You have no idea how hard that is. Normally, we rely upon well-worn social scripts and rules yhat are well understood. It was not until we were back in the West on our way home that we comprehended the cultural pressures we had experienced.

In addition, the isolation seemed crushing over time. There were no cell phones or visual media or easy ways of contacting the outside world. There were a telephone or two at the government facilities, but one could not escape the sense of being totally on your own. I recall realizing how much I missed the college sweetheart I left behind (being quite commitment-phobic). I wrote often, but she wound up marrying a post-doc at Harvard where she was working at the time. Who could blame her? Decades later, we reconnected. It was only then that we realized we had loved one another back then but were too damaged to recognize that fact. She speculated how different things might have been had there been modern communication technologies. Roads not taken and all.

Most disconcerting is that we volunteers never felt confident in our primary role. You can’t become a farming expert in a few weeks (especially when expected to learn a new language, cultural nuances, and the complexities of village life). Most of us never escaped that nagging sense that we were frauds. What rendered that sense particularly critical is the awareness that our mistakes might have profound consequences.

On the other hand, we got to experience something unique. The town located about a mile from our isolated accommodations was called Salumbar. It was of decent size (though still a comparatively smaller town) that was situated amidst a harsh and unyielding desert. While some affluence was to be found, many farmers in the area ecked out a marginal existence on tiny plots of land. It was a level of want and vulnerability I had never witnessed in my young life, nor since.

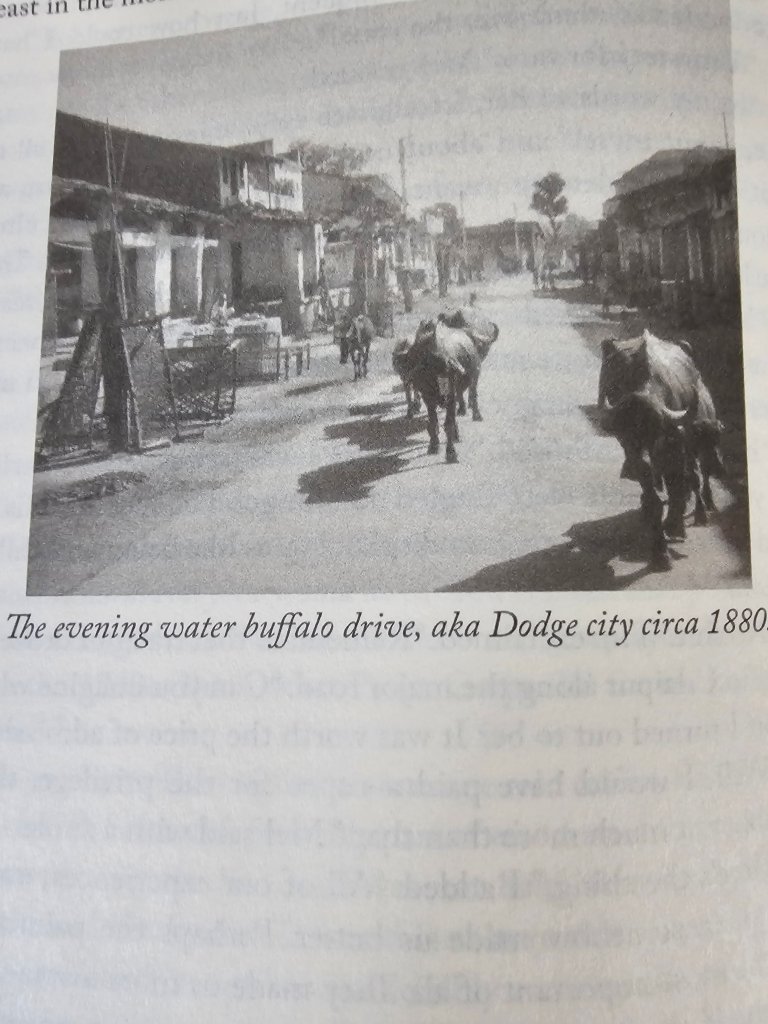

I could never quite escape the sense that I was living in the past. To me, Salumbar looked like a western frontier town of the 1870s. On occasion, farmers drove their water Buffalo through the streets or rough looking men would ride though on camels while sporting rifles and wearing cartridges across their chests as if off to war. Was Pancho Villa preparing a raid?

But mostly we did try to ply our trade as best we could, trying out several ideas we thought might prove useful. We erected a chicken project demo, raised money from my college back in the States to restock the local school library, and developed a home garden demo, among other initiatives. Mostly, though, we tried to convince local farmers to try new forms of hybrid seeds that would greatly enhance yields. This was part of the ‘green revolution’ launched in the third world by Norman Borlaug. It was seen as a possible rescue for an India facing exponential population growth with constrained resources.

We did have successes. You can see in the pics above a successful demo plot along with me tending our demo home garden. Frankly, being a well-known klutz, I cannot believe I erected a chicken coop on top of our home. Astonishingly, I successfuly raised several vegetables. Who was that guy?

Still, the challenges were many, too many to recount here. One will suffice. These new hybrid seeds demanded that the farmer adhere to a set of strict protocols including how to plant the seeds correctly, how to fertilize the crop, when to water, and so forth. In the past, these marginal farmers could throw out some seed left over from last year yield and (usually) get a crop that would enable the family to survive.

These new hybrid seeds we were hawking held the promise of previously unheard of yields. To obtain this bounty, however, the local farmer had to make an upfront investment of money and follow a set of practices that demanded unusual care and attention to detail. Even then, success could not be guaranteed. For example, the promised wonder seeds might have been adulterated along the way (good seed stolen to be replaced by crap). Corruption was endemic.

That left us volunteers in a dilemma. Should we work with the poorest of the poor. I wanted to. But they spoke a local dialect (Mewari and not Hindi which I had learned). The chances of miscommunication were great. Worse, if something were to go wrong, there was no plan B. There was no crop insurance nor a government safety net. Which of us could bear the guilt of pushing a marginal farmer (and his family) over the financial edge. So, we tended to work with better educated, hoping that change eventually would trickle down to all. In the meantime, we risked exacerbating local inequalities.

Did we do any good? Who knows? I will say that India was a grain importing nation in 1967 when we started our tour. It was exporting grain by the early 1970s. Of course, that turn around was more likely due to the return of the life-giving monsoons than to our poor efforts.

I can recall feeling very pessimistic about the future of the country back then. I could not imagine how these marginal farms would survive over the next generation or two. Most farmers had large families. In the past, they needed many offspring so that there would be surviving males to support them in the future. But with improved public health, many more children were surviving to adulthood. The existing family farms were too small to split any further. How would these children survive? What would they do?

Was an apocalypse in the making? Fortunately, that did not happen. The bottom half of the picture of our local home above presents what that same place (our government site) looks like today. The desert has been replaced by growth, new buildings and developments, and green fields brought to life by irrigation. India is taking its place among the more developed countries in the world.

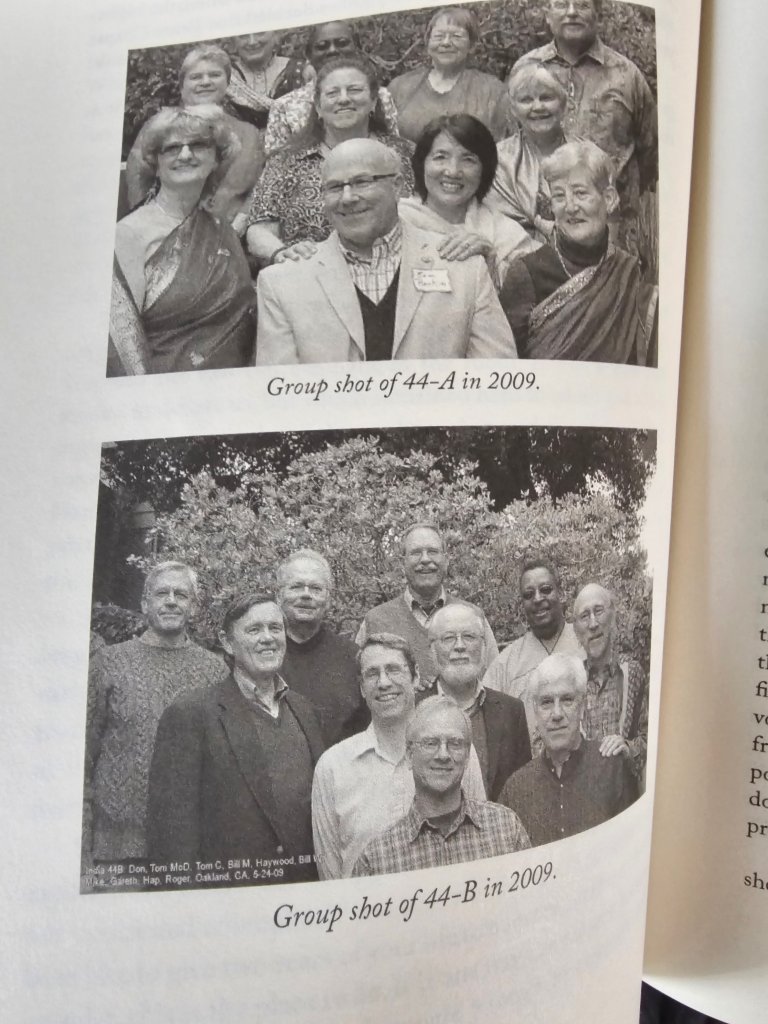

Above, we have most of the survivors from India 44 (A and B) taken at a reunion some 40 years after our return in 1969. By way of explanation, India 44-A was a public health group (mostly female) who were assigned to the State of Maharasthra (near Mumbai, Bombay back in the day). We guys in India 44-B were yhe so-called Ag experts. We were dropped in the arid land around Udaipur in southern Rajasthan. But we all trained together and formed a common bond.

I doubt whether our brave band who ventured forth in 1967 can take much credit for any observed successes. But we all know that each of us took so much away from that experience. As mentioned, the accomplishments of these volunteers have been remarkable. It is hard for me to decide whether Peace Corps did a remarkable job in selecting talent or something about the experience added value to our subsequent lives. Perhaps someone else can solve that conundrum.

I can yet recall sitting on top of our house at night, the roof could only be accessed via a rickety ladder. Nothing but desert could be seen from our vantage point. The evening would be most pleasant after another scorching day with temps oft pushing 110 or higher. But the night air was refreshing, and the sky would be blazing with stars. The pace of life about us was glacial … so much time to read and think and simply appreciate a world that we (so busy in our western, adult lives) tend to ignore. All in all, it truly was a time out of time.

It is too bad that more young people do not have access to such an opportunity.

2 responses to “Continuing the Grand Adventure …”

Ya know, we have and continue to enjoy your rantings and over all those years and continued friendship, here we thought you were a real fuck up. lol Now we know better and are duly impressed. B & A

>

LikeLike

No Brian, you had me pegged correctly … a real luck up 😀. Thanks for the comment.

LikeLike