I once concerned myself with the issue of poverty. You might even say it was a personal obsession. After all, I was affiliated with the nationally renowned Institute for Research on Poverty (IRP) located at the University of Wisconsin. In fact, I served as the Institute’s Acting and Associate Director for about a decade before starting to gradually retire from my professional career in 2002.

I also taught social policy courses at the undergraduate and graduate levels while consulting with many states and localities across the U.S. and Canada. Much of this consulting work focused on the design and efficacy of their human services systems. I spent so much time in Washington that some federal officials joked that I really worked in our nation’s capital, and not at the UW in Madison. While my professional interests always remained eclectic, and my intellectual portfolio was very broad for a nominal academic, the issue of poverty was never far from my core interest.

Poverty … the lost issue.

I haven’t given the issue much thought, nor any attention, for some time now. Perhaps that is due to the realization that, in the U.S., poverty has virtually ceased to be a major public issue. The late UW economist Bob Lampman (whom I greatly admired), a scholar credited with writing the chapter in an economic report to then President Kennedy that inspired the subsequent national War on Poverty, once noted the following: ‘In the 1960s, public policies were subject to the following litmus test … what does it do for the poor?’ Such a perspective seems quaint, like lost ancient history, in today’s political world.

Our concern for the vulnerable and disadvantaged, a front- burner topic in the 1960s, faded with time. By the 1980s and 90s, President Johnson’s declared war on poverty (1965) had devolved into what many saw as a war on the poor. A so-called public ‘war’ yet raged but mostly around what to do with those dependent on public benefits. Conservatives had seized the policy narrative on this issue.

The welfare ‘reform’ battles during those decades were waged with unremitting ferocity. It became one of the primary fronts in the emerging and vitriolic political contest between the left and the right. This would be a contest where the sides would pull further and further apart with an ever widening ideological chasm separating the two camps and their competing perspectives. Poverty and welfare became part and parcel of the ferocious culture wars.

Today, I am taken with just how central the poverty and welfare debates were back when I was fully involved in state and national policy debates. Seldom did a week go by when I was not contacted by the national and local press to comment on the latest policy kerfuffle about the welfare crisis. The number of public engagements I received to talk about these issues seemed unending, the opportunities to consult with policy types unceasing, and the number of trips to DC never diminished (including one full year working on President Clinton’s reform efforts).

The intensity of the feelings on the part of policy combatants became increasingly entrenched and virulent. In short, the poverty and welfare questions were not for the weak of heart nor those seeking popularity. I once joked to the man in charge of Wisconsin’s welfare programs that I only sensed I was approaching the truth within this policy cauldron when no one else agreed with me. Still, for better or worse I found myself at the very center of it all.

And suddenly, it surely seemed sudden to me at least, the poverty-welfare question dropped from public view. After the entitlement to cash assistance for poor families largely ended when the 1996 federal reform law was signed into law (an Act where TANF or the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families program replaced the old AFDC system), observable interest in the poor gradually ebbed. The worst projections of what might happen to those families losing their entitlement to cash assistance never materialized. Within a decade, most no longer cared.

As we moved into the 21st century, less and less attention was paid to those at the bottom of society. Partially filling our attention gap were growing concerns about income and wealth inequality and the hollowing out of the middle class. These issues never quite enraged the public, nor politicians, as either the welfare question had in my day nor the poverty question during the 1960s. Still, the time when hyper-inequality becomes THE issue might be near. More on this later.

A startling new poverty line?

So, it was with interest that I read about the reaction to a piece published by investor Michael Green. The headline read that a family of four would need an income of $136,500 per year to escape want. This figure struck many as shocking. After all, the official poverty level for a family of four is pegged at $32,150 per-annum while the medium family income figure in the U.S. is $83,730. To make comparisons more appropriate, I should mention that the median income level for families with at least two kids recently has been estimated at $109,300. Green’s so-called poverty line is above all of these figures.

On first glance, it would appear that well more than half of all families with kids are ‘poor.’ But this clearly doesn’t pass the proverbial smell test. To make Green’s headline-grabbing figures work, certain assumptions are essential. For example, the family would need full-time, paid child care. According to his considered calculations, his hypothetical family of four would spend some $32,700 per year on childcare alone. On its own, this expenditure is slightly more than the official poverty line. Moreover, this child care outlay makes assumptions about the ages of children and whether alternatives to full time child care are available. Then again, one can quibble about the efficacy of any measure.

Overall, I would assess Green’s exercise as defining a ‘comfort’ level, more like a ‘living wage’ figure, than a poverty line. Nevertheless, it might well explain why families with solid, middle-class incomes feel anxious and insecure. And it might help us understand why so many feel that the economy is troubled despite low unemployment and near record equity prices.

In fact, other estimates of a hypothetical living wage come up with similar figures. An MIT estimate for a similar ‘living wage’ in a typical state (Maryland) is $129,600 while the Economic Policy Institute pegs the figure in the D.C. area at $139,500. In that sense, Green’s offering is not out of line, and far from outlandish.

But here is the rub, or one of them at least. Our metrics for assessing well-being have always been controversial. For instance, we really don’t have a consensus on what poverty is, nor how to measure it.

One of the many windmills toward which I tilted my reformist lance during my foolish youth was the officially designated poverty line, the income point that our federal government claimed separated the poor from the non-poor. It was formulated in the early 1960s by a middle level bureaucrat (Mollie Orshansky) who labored in the Social Security Administration at the beginning of the War on Poverty. This public war on want needed a measure and she was assigned the task. After all, you cannot wage a war on somethimg that has not been satisfactorily defined.

What did Mollie do? She took a Department of Agriculture study that monetized the cheapest food basket for a typical low-income family configuration. Then, she found another dated study which suggested that a lower-income American families spent one-third of their budget on food. So, Mollie multiplied the cost of her cheap basket of food goods by a factor of three. Next, an equivalency scale was developed (to account for different family sizes) and those figures were adjusted over time for inflation.

Viola! We had a national poverty measure, one on which many ancillary decisions were based, including how to distribute scarce federal dollars across states and localities. This measure was little more than a back of the envelope exercise. At the same time, it was far more than an intellectual, or casual, calculation. It had real policy consequences.

Even though she was long retired, Mollie attended some meetings in the 1990s at which I was present. She made it abundantly clear that she assumed what she had done would be a short-term expedient. Surely, a more sensitive and accurate measure would soon be developed. But, other than small, technical tinkering, none was. She remained shocked and saddened by that fact.

Certainly by the 1990s, no one defended the official measure any longer. The flaws in the measure were obvious and endless. By then, the cost of an essential basket of food stuffs would be multiplied by 6 or 7 times, not the factor of 3 that Mollie employed. With resources from the Casey and Mott Foundations, I and several of my colleagues at the Institute and in D.C. set about to improve the official poverty metric. It was a long, complicated process that, in the end, had mixed results.

The political head winds that prevailed by the time of the Gingrich Congressional revolution (1994) made any rational discussion of even the most technical issues quite infeasible. Despite our efforts, replacing the official poverty measure with something sensible proved impossible. That experience proved a prescient harbinger for where our once rational policy world was headed.

However, all was not in vain. The work we and others did resulted in the creation of a few supplemental measures that made several improvements. Among other things, they more accurately assessed the costs of living in poverty and in calculating the resources available to the poor, especially non-cash or cash-equivalent benefits. These supplemental measures never replaced the official standard but now are routinely employed by the press, academics, and others. Recently, the poverty level for a standard family is pegged at about $39,000 according to a widely used supplemental measure, some $7,000 above the official rate.

Still, it must be acknowledged that assessing poverty, and what it really means, will remain a subjective and contentious issue. In earlier meme (above), we see that most Americans are pessimistic about our economy even as equity markets approach historic highs and employment levels remain robust (for the moment). Basically, perception is everything.

An illusive metric.

Not surprisingly, how one thinks about poverty varies dramatically. If you look beyond the U.S., you can find several alternative approaches, some not even based on cash resources. Remaining with income- based measures for the moment, we might consider the following:

- Relative measures of poverty … many countries employ what are termed relative approaches. They set their poverty lines at either 50 or 44 percent of the jurisdictions median income figure. Such measures are more sensitive to the distribution of resources and how far one is from the typical or modal family.

- Subjective measures … a few European countries explored poverty lines based on a consensus about the minimal income level a family like theirs would need to just get by. This survey-based approach assumes that respondents (real people) are the best arbiters of what poverty means.

- Poverty gap measures … Rather than setting a line that separates the poor from the non poor, a gap approach calculates the distance each family is above or below said line. This makes it easier to measure extreme levels of poverty and family units who fall into the near poor category. Proponents argue that having income one dollar over or under an artificial line does an inadequate job of differentiating the poor from the non-poor.

- Some argue that poverty is best measured by expenditures, not income. A family may not have observable sources of income yet have access to resources. Their capacity to purchase goods and services is what ultimately matters. Perhaps that should be our focus.

- Asolute measures. This is the standard approach. You somehow calculate an amount a family needs to survive, as Ms. Orshansky did in the 1960s.

We also have non-income measures:

1. Social exclusion measures … Europeans, in particular, often discuss poverty in terms of social exclusion. Such measures tap an individual’s or a family’s isolation … a lack of access to the social capital required to fully participate in society. You are impoverished if you are not minimally integrated within society’s essential networks.

2. Human capital deficits … this concept focuses on measuring the hard and soft skills necessary to being an independent, productive worker and a contributing member of society. Hard skills are vocational in character. Soft skills focus of acceptable behaviors and interpersonal skills. If you haven’t got the skills, life will be challenging.

3. Specific resource deficits … here we focus on shortcomings in specific areas of life. For example, some measures focus on food insecurity or various metrics tapping the individual’s ability (or inability) to secure adequate nutrition and nourishment. Shelter insecurity focuses on homelessness or inadequate housing (overcrowding or unsafe abodes). Others are possible.

4. Social mobility measures deserve more attention than they typically receive. A hallmark of the American dream is that anyone can make it if they try. Yet, as inequality here has increased exponentially and the costs of education and other traditional tactics for success have become less accessible to many, social mobility in the U.S. has congealed. Recent research has indicated that inter-quintile movement (a measure of social mobility premised on the ease of moving up or down the income scale) is higher in many European nations than in the U.S. Want the traditional American dream today? Go to one of those socialist Scandinavian countries.

These various conceptual approaches capture our confusion about what it means to be poor. In any case, income measures remain the most popular despite their limitations and flaws. In the end, monetary measures simply are easier to calculate.

A matter of choice.

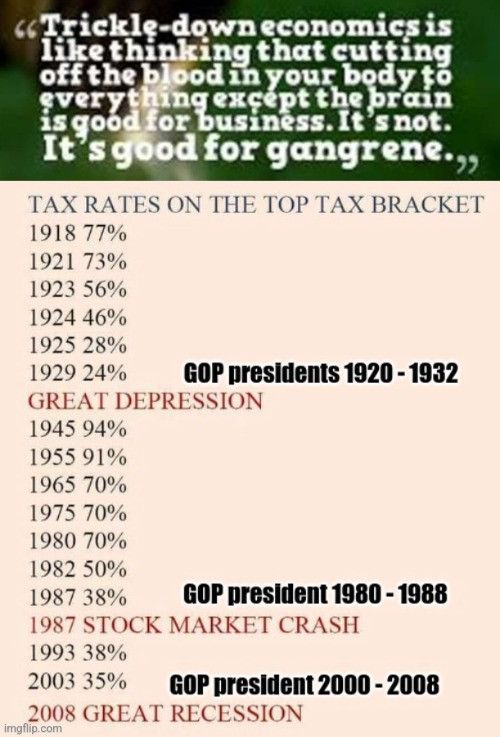

Poverty policy really is a matter of public will. In short, destitution is not inevitable, despite the biblical assertion that the poor we shall always have with us. Public budgets have long been seen as morality documents. How much we tax the winners in society and how much we spend on others are moral decisions. From the meme above, we can see that our willingness to pay for public purposes generally has diminished over time. Does this reflect a national moral failure? Is it not odd that policy debates oft focus on reducing public expenditures rather than demanding that the wealthy pay that share they once contributed to the public good as a matter of course? That question must be saved for another time.

Let’s start this section with the assertion that any single poverty number you might see in the press is what I term a ‘so what’ figure. For example, the most recent U.S. poverty rate is 11.1 percent, or 38.6 million citizens. But is that good or bad? As with most social indicators, we need comparative numbers to assign any real meaning. Three example comparisons that might be made are: 1) against a specified target; 2) progress over time; or 3) our position relative to selected peer nations.

1. Target-based assessments: One might establish a target or goal within some national or public effort. I don’t recall Lyndon Johnson stating that his war on destitution would eradicate poverty entirely, but he might have implied as much. At the time, however, one Nobel- winning economist (Robert Solow as I recall) did predict that U.S. poverty would be eliminated by our Bicentennial year, 1976. More recently, British PM Tony Blair set a national goal for eliminating child poverty in the U.K. within a generation. Against such an ambitious goal, a poverty rate of 11 percent, or any figure above zero, would be judged a policy failure. Then again, Tony knew he would no longer be PM in a generation’s time.

2. Temporal assessments: One might examine rates over time. Are we doing better or worse while using past performance as a baseline? After early progress against poverty in the 1950s and 60s, progress against poverty stalled in the U.S. When measured by the official rate, between 11 and 15 percent of the population have been designated as living below our poverty line over several decades, the rate for children consistently being higher. (Note: U.S. poverty did fall dramatically during the recent Covid pandemic when significant stimulus checks and other benefits were distributed to resuscitate the economy).

Similarly, the numbers of official poor has fluctuated between 35 and 50 million citizens without any singular trend in a given direction. In fact, today’s rate of 11.1 percent is the same as the rate measured in 1974. Viewed temporally, progress against poverty in the U.S. is difficult to find after our early successes.

3. Comparisons with peer nations: If we compare our performance against those of nations we consider our peers, the American performance decidedly suffers. Over the past several decades, the scorecard comparing the U.S. performance against virtually all advanced democracies positions us poorly among international scorecards. Scandinavian countries, in particular, do a much better job. During years when child poverty in the U.S. approached 20 percent, the child poverty rates in countries like Sweden and Denmark were well below 5 percent. The U.S. consistently places at or toward the bottom in such quasi-global rankings.

Another interesting story comes out of China. The World Bank estimates that 88 percent of all Chinese were considered destitute in 1978, just before their decision to deregulated much of their economy and invest in national growth. Today, that figure has fallen to less than 1 percent. The lesson … political will matters. Economic want can be lessened if the public demands such or government decides it is worth the effort. Progress becomes less likely when policy is viewed within a zero-sum framework. Then, the affluent see efforts to help the poor as inevitably resulting in losses to them.

Some big questions!

The poverty conundrum raises several big questions, for me at least:

A. Will redistribution issues replace absolute monetary deficits as the new basis for addressing poverty. I don’t see non-monetary metrics for assessing poverty (e.g., social exclusion or human capital deficits) replacing our customary measures. But I can see more attention being paid to distributional notions of well-being or how resources and opportunity are allocated across the society. Already, more attention is being paid to inequality (as opposed to conventional poverty) these days. Perhaps the gini-coefficient (a measure of income or wealth inequality) will become the new standard. It is hard to ignore reports of $50 plus trillion dollars bring redistributed from the bottom 90 percent to the top of the income pyramid in the U.S. Hyper- inequality also suggests a choking off of upward social mobility. Nothing will rile people up more than the loss of hope.

B. What happens when technology makes labor irrelevant? Will the less skilled (or even the more highly skilled) become little more than a burden in the future. Even now, we anticipate AI replacing untold millions of jobs over the next generation. I spoke about this issue in 2013 when I gave the plenary talk at an IRP conference to academics who teach university-based poverty courses around the country. I stressed that new digital and robotic technologies will utterly restructure our future labor markets, thus impacting our wellbeing in ways we could hardly imagine. That day is now upon us. As with earlier technological revolutions, perhaps new opportunities will emerge. But that is not certain. I fear what will happen to the displaced when they are no longer necessary. We don’t treat the poor well now even though we still need most of them. What will we do when we don’t?

3. What has been the legacy of our long ago War on Poverty? Most pundits, if they remember it at all, have doubts about its success. That sense of failure tends to discourage similar efforts or even any positive rhetoric. After all, poverty in the U.S. has seemed stagnate for the almost three generations since President Johnson declared our national war in 1965. This sense of failure persists despite the expenditures of considerable resources and energy.

Yet, there is another way to think about this last conundrum. Despite America’s fractured and under-resourced social safety net, perhaps our ‘war’ against poverty has been more successful than we imagined. Consider all the headwinds we have faced in recent decades. There have been changes in demographics (more single-adult families), in immigration (increases in lower-skilled workers), in technologies (worker displacement), and in global competition (more outsourcing of higher paying jobs to other nations), to name just a few exogenous trends. Absent our attempts to help the poor, as weak as they may have been, our situation may have been much worse. Perhaps we have not failed as much as some argue. It is something to consider.

Once again, I’ve probably gone on too long. I should end here. But I’m sure to return to this topic in the future. I bet you can’t wait 😏 !

One response to “The Poverty Question(s).”

The Soviet Union was what happens when a socialist society is taken over by gangsters.

The USA is what happens when a capitalist society is taken over by gangsters.

LikeLike