As with some interpretations of the sub-atomic world, we merely are what we seem to be at a specific point in time. In a sense, observation helps create what we perceive as real. Physicists immersed in quantum mechanics are captured by the uncertainty of our tiniest physical properties. Are these unimaginably small packets of energy to be thought of as waves or are they discrete particles? Can you ever perceive them accurately or do they remain elusive, remaining just beyond our apprehension?

Like a befuddled physicist, I’m reflecting on my own evolving perspective of personal truths over time. Much as those seers into the mysteries of nature (those theorists whom we seldom understand), this is an uncertain venture. Memories are, I fear, fickle phenomena. Are they altered by our very act of recalling them to the surface of our consciousness? Can we be certain they are real? In the end, do we create our own history?

I can recall my Peace Corps group as we struggled to recall our individual experiences while putting together two edited volumes about our service in India in the late 1960s. Now that was an eye-opening experience. Our effort to recreate our tenure on the subcontinent took place some four decades after our return. It proved an elusive task. It soon became a test about whether any of us can explore our pasts with any authenticity.

The members of my PC group (India-44) would share memories, verbally when we met as a group or in writing when we were apart. These initial recollections were based on what we could summon from our deeper recesses. Soon, however, doubts about the validity of our memories inevitably surfaced. Many arose when inconsistencies emerged in the retelling of what were thought were common or group experiences.

Some of us then took a second step … looking about for diaries or letters to confirm our individual recollections. To my lasting chagrin, I never kept a diary, one of the few regrets I yet carry with me. Some of my peers did, however. Still others retained letters which served a similar purpose. Not surprisingly, I had none of those either. Bad Tom.

In this instance, however, I was bailed out by serendipitous fortune. Fortune has always exceeded my common sense and certainly my meager talents. During my service overseas, I kept up an active correspondence with the one girl from college for whom I had fallen for in extremis, what can only be described as a head-over-heals emotional attachment. Though I saw myself as above such pedestrian or mortal feelings, she had brought me to my knees.

This embarrassing weakness only ceased (sort of) when she sent me a classic Dear Tom letter while I was enduring a lonely existence halfway around the world. In it, she informed me that she was marrying a post-doc she met while working at Harvard. I was both shattered and relieved.

To put this in context, I had fallen totally for this gal … I mean a raw, irrational infatuation. Such an emotion was utterly foreign in my experience given that I was one of those for whom commitment and marriage were the equivalent to a quiet, if permanent, form of death. Running off to India had seemed like a great idea at the time. It was a form of escape from what I envisioned to be a dire, perhaps irreversible, fate.

To make a long story short (too late), we reconnected after some four plus decades of no contact. Ah, the miracle of cyberspace. By reconnecting, I mean in a virtual sense, not physically. But it gave us an opportunity to reassess our stupidity as young kids. We rediscovered the character and depth of our youthful feelings and why we both were so intent on repressing them. It turned out that she was as damaged as I. Fortunately, I stumbled across her just in time. She would pass away from cancer after a couple of years.

One outcome of this late-life reconnection was the discovery that she had saved all those letters I had sent her from India along with other momentos from our youthful, star-crossed association. Communicating with her again reminded me that those wistful memories of her that I had carried with me through the years had been rooted in something substantial and real. It was also gratifying to discover that I retained a special place in her heart. Shockingly, it turned out that she had and (still) did love me, at least to the extent that each of us was capable of such foolishness. We were way too fractured and insecure to voice such conventional sentiments in our youth. Though it made no material difference to where we were so late in our lives, it was gratifying to finally know such things.

On the other hand, the correspondence she shared with me decades after they were written were an eye opener in many instances. For example, I had long entertained the notion that I proposed to her in writing about halfway through my Peace Corps service. In that version of events, my proposal missive and her Dear Tom letter crossed paths somewhere over the oceans … a true Hallmark movie script. But no, I had raised the prospect of matrimony very early on. For reasons that baffled her in later years, she managed to block my rather pathetic entreaties … and indeed they were most pathetic. I put her reaction in this matter down to her innate common sense. At that point in life, I was hardly a catch. Then again, I never improved much in that regard over time. She, on the other hand, was perplexed and saddened that she missed what I was trying to communicate … she somehow had blocked my expressions of commitment from her awareness. But there they were, in black and white.

Our correspondence had continued throughout my service, even long after she had chosen a different life path. These letters remained my only real time evidence of what I was thinking and doing back in the day. For those of us in India-44 fortunate enough to have letters and diaries, we all scoured the available documents to compare their contents against our cherished, often long held, memories. After all, our service constituted the most intense experiences of our young lives. For us, Peace Corps was the equivalent of going to war, a time out of time where we had tested ourselves.

We dived into this reexamination of our past because we had decided, as a group, to write an edited book summarizing our overseas service … a project that ended up as three volumes (two group efforts and one I wrote solo). The results of our ruminations, oft times, were rather shocking but also quite revealing.

In many cases, our real-time writings documenting our former lives contradicted our accepted priors. If there were a pattern to these systemic distortions of the past, it leaned in the direction of painting a less flattering version of our service. We tended to forget or suppress our contributions in favor of retaining shortcomings and embarrassments. That seems counter-intuitive but there you have it. In short, we tended to recall our failings, which were many while neglecting our successes. Perhaps the expectations we imposed on ourselves were overly ambitious.

I share this rather lengthy introduction to stress that memories are fickle, perhaps more of a projection of wishes and neuroses than anything close to a depiction of reality. On the other hand, our recollections, no matter how distorted, generally are what we have remaining to us in our dotage. After all, we spend enough time pondering them.

Given all these caveats, I still do have a story. Its authenticity might be questioned but, in the end, it is all I have. It is all most of us have. It is a story of radical transformation and yet surprising consistency. Below, I give you the barest contours of my early journey, or at least my start in life.

I was a most conventional child, a totally average working-class Catholic youth of Irish-Polish ancestry. Without siblings, I learned to live within the boundaries of my own imagination even though the street outside our modest flat was replete with other undisciplined urchins. I must confess, though, the world inside my head was a fascinating place.

It also was an innocent time. We roamed the streets unsupervised, our only restriction being to return home by the time the streetlights came on. I could have been kidnapped by miscreants and ravage by perverts several states away before anyone realized I was missing. Perhaps that was my folk’s plan. If so, they were to be disappointed, as were all the other parents. No one seemed interested in kidnapping me or any of my partners in crime.

I grew up in a cocoon … a white, Catholic, blue collar world or what might be considered an insulated bubble. We revered the Pope in Rome, along with our Parish priests. We recited the pledge of allegiance in class, occasionally diving under our school desks as if they would protect our skinny asses if the Russkies decided to drop the big one. We really believed we were the good guys, the last bastion of freedom preventing the godless Commies from dominating the world. And we were true-blue Democrats since our domestic enemies were the Republican WASPS who lived in luxury on the other side of town. Somehow, they were responsible for our economic struggles.

My world was very tribal. On meeting someone new, you were asked what are you? Responding with your ethnic identity let the inquirer position you in the consensus social hierarchy shared by all those you knew. The world, indeed, was a fixed and ordered place. We all knew our position in that world.

I recall being a tot tagging along with my dad one day. A friend of his asked me the big question, what are you? Being too young to understand, and considering that I spoke English, that’s how I responded to my inquisitor… I’m English. My dad, a true Irishman having been born in South Boston, gave me the big lecture on why we Irish hated the English. That must have made an impact since that memory, real or not, has been part of me for almost eighty years.

My early world was a complex mesh of divisions and prejudices. It was not just black and white or Catholic versus pagans but a world where every conceivable group was assigned a place in an arbitrary, though rigid, hierarchy of status and worth. It was a world of excessive judgment that I would soon come to disdain and then reject.

It was not until high school that I sequed from the local public school system to an all-boys Catholic institution. St. John’s Prep was the best Catholic high school in central Massachusetts. Though I had been placed in an advanced class in junior high, I always considered myself an average student at best. In truth, I thought myself rather a dullard though I did like to read.

I attacked whatever I could get my hands on. My dad received volumes from the Readers Digest condensed books series which I consumed religiously along with the Encyclopedia Btitannica that we had in the house. I secured my library card early on, not an acquisition to be shared with my my street mates for fear of provoking their derision. After that, I was a regular visitor to that local establishment. In any case, I was not optimistic about my chances of being accepted into this prestigious institution. Shockingly, St. John’s did accept me. I was further stunned that I had been placed in the top class based on the results of my entrance examination.

I had a full blown case of the imposter syndrom. This absence of self confidence proved an affliction that would dog me throughout life. There likely are several causes for this curse though I tend to reject singular explanations for most things. Yet, one factor is difficult for me to ignore.

My mother was an extremely insecure and unhappy woman. I always felt she viewed me as a commodity to be paraded before others, mostly as a tactic to garner praise. I always felt on display. In consequence, she kept finding imperfections and faults in me. It was not until I was an adult that I discovered she praised me to the skies behind my back. I, however, can’t recall any of that. I only remembered the constant criticisms. Apparently, that left me with this pervasive sense of personal inadequacy.

At St. Johns, I cannot say that I stood out at all. What I do recall is that I spent four years arguing with my theology teachers (only within the safety of my own consciousness) about various aspects of my Catholic religious heritage … the parts that made no sense to me (e.g., birth control). That should have been clue number one as to my future as a Catholic or follower of any religious tradition. But it didn’t.

It was a good school academically, the competition was intense. I eventually would go on to earn a doctorate at an R-1 university (a top research school) but always felt high school to be my most serious intellectual challenge. My late wife, who graduated with honors from a respected law school, felt the same about her Catholic girl’s high school in the Twin Cities. We both studied hard but never stood out among our peers.

Nevertheless, I fought off the religious doubts that arose within me to enter a Catholic Seminary (the Maryknoll missionary order) upon graduation. I had decided that a life dedicated to serving others in foreign lands would be something worth pursuing. I tried to be a good Priest in training, but to no avail. It took me a little over a year to appreciate finally that I did not possess the basic job requirement to be a Priest … a belief in a personal God. I realized that I wanted to give people hope, not save their souls.

Leaving the seminary and winding up at Clark University back in my home town would prove to be the turning point of my life. This would be an unusual transition to say the least. Within the Catholic community, Clark was viewed as a den of atheists and communists. Still, after some 19 years within a hermetically sealed intellectual bubble of cultural orthodoxy, such an exotic option suddenly looked to me like an inviting prison break.

Moreover, a bit of serendipity was involved in getting to Clark. Being poor, my choices were limited to nearby institutions. The excellent Jesuit run College of the Holy Cross would have been my first choice had I gone directly on to college from high school. Clark wouldn’t have entered my mind. While virtually all my high school classmates had gone on to college, I cannot recall a single one matriculating at Clark during this period. It just wasn’t done. It would be considered too great a threat to one’s faith.

But Holy Cross didn’t accept Spring semester applicants while Clark did. That was all the excuse I needed. So, in the Spring Semester of 1964, I started my new life outside the secure embrace of a protected, insular childhood. I suspect it took me two weeks, if that long, to shed my conventional religious beliefs. It all happened seamlessly, absent thought and certainly without struggle. It was as if I had been waiting for this moment all of my life. Shedding the remainder of my cultural baggage took longer, and involved more personal struggle.

By the ‘remainder of my cultural baggage,’ I’m primarily referring to the set of beliefs that were shared and reinforced by all around me. It was an innocence and naivete that stems from the vanilla, homogenous patina in which my belief system was covered. America was pure, our democracy was pretty much perfect, we had a monopoly on virtue and goodness. After all, I had grown up reading books like Masters of Deceit, a clever piece of propaganda purportedly written by that famous defender of American moral righteousness … J. Edgar Hoover himself. Nominally, for me at least, the world was black and white with few shades of grey.

I cannot recall many transitional events, moments of experienced epipanies. But the drips eroding my heretofore congealed beliefs came with increased frequency. I don’t believe anyone challenged my world view directly. Mostly, it was an osmotic process of absorbing new facts and perspectives within the questioning intellectual environment in which I suddenly found myself.

Oh, I would now read that American operatives overthrew leaders in other countries because we didn’t like their views. Or I would become increasingly aware of our apartheid regime in the South, or our use of concentration camps for loyal Japanese Americans in WWII, or our cavalier practice of genocidal policies toward Native Americans and their traditional culture. I cannot recall anyone, certainly no professor or authority figure, pointing out that such things were wrong. What mattered is that, for the first time in my life, I found myself in an environment where questions were more important than answers. The search for truth had more meaning than responding to everything with approved certainties. It was a thrilling, if unsettling, experience for me.

My current next door neighbor grew up in a household where his father was a distinguished academic. In his youth, he was surrounded by eminent historians from the University of Wisconsin. Many decades ago, he asked one of them what the purpose of a liberal arts education might be. The response he received … you won’t be easily fooled. That was what I was learning at Clark, how to think for myself. I would not longer be easily fooled. Now, really for the first time, I loved learning.

While I had shed any institutional affiliation with organized religion, I had not dismissed the moral center that I had embraced in my youth. Christ, as a spiritual teacher had always made sense to me, as had many proponents of a moral life from ancient times. The lessons of love, acceptance, and compassion are timeless. They endure beyond the silly rituals and childish myths that degrade and overly simplify the essence of a more universal spiritual experience. Like the Buddha taught his disciples some 500 years before Christ, spiritual truth lies within each of us. We merely have to find it.

Suddenly, life made sense. My religious excursion merely was an expression of this need to contribute to society. So, to support my education, I found work as an orderly on the night shift in an urban hospital, then working with disadvantaged kids, and (upon graduation) pursuing two years of service overseas in the Peace Corps.

But it also meant fighting back against what I increasingly viewed as the sins of my own country. The process of detaching myself from my childhood innocence subtly shifted my feelings from a sense of disenchantment to anger. Yes, I felt betrayed. I could not shake the sense that I had been lied to, and by those whom I’d been raised to trust, if not revere. If there was one moment of no return, it involved my rejection of the U.S. role in Vietnam.

It was the issue for white boys of my generation. For most, it could be a matter of life and death. Beyond that, the issue also tapped our deepest feelings of patriotism and responsibility and self-worth. Yet, the more I read and analyzed, the more my doubts increased. Still, was opposing the war based on credible analysis or merely convenient self-preservation? Were our policies bankrupt or did they constitute a reasonable response to a mortal threat? We were all pulled in many contradictory directions during this confusing time.

I read on the topic voraciously. My peers and I discussed the issues far into the night. We occasionally attended teach-ins and lectures. Deciding where we stood was not easily arrived at. In an earlier blog, I recounted my day long discussion with a fellow super bright student whom, like me, had been awarded a National Science Foundation research summer grant for promising psychology undergraduates. Our debate occurred early in the War when support remained high. It was my last and final effort to retain my old set of beliefs. But I could feel them crumbling throughout that long day. At the end, I knew I could no longer preserve what my world view had been.

Soon, I would organize the first anti-war student group on campus. We led discussions and marches and other activities to educate the broader community. The early protests were not easy since we were attacked as disloyal, if not actual Commie dupes. Protests would later segue into more aggressive forms of resistance but I was gone by then. Besides, that would never have been my style. I embraced the teachings of Ghandi and Reverand King including a form of liberation Catholicism (which probably no longer exists) that I found attractive from my childhood.

In a very short time, I managed to shed one persona while adopting an entirely new one. I had transitioned from a compliant youth who remained true to his cultural baggage despite occasional doubts to a young man struggling to create his own personal world view and moral code. I learned one thing very quickly. It is easy to embrace that which is given you. It is hard, but so rewarding, to struggle toward your own set of beliefs.

I can never quite decide whether my accidental arrival at Clark University was responsible for my individual awakening or whether I would have gotten there in any case. Part of me says that we all have an initial internal wiring that may not determine outcomes but which makes some life trajectories more probable than others. For example, some of us are blessed with brains that can deal more easily with new stimuli while others find anything unfamiliar to be more of a threat. Similarly, some of us welcome dissonant input as a way learn new things while others easily dismiss anything contrary to their existing world view. As a college teacher I preferred to challenge the priors of my students. You dont learn much if your preconceptions are simply reinforced.

I’m not sure about this but I sense I’ve been graced with a couple of what I call connective capacities. One might be called an emotional attachment to others. I always had this sensitivity to what others might be experiencing. I suppose we might simply term this attribute as empathy.

The other is a more cognitive- focused capability. I really am not a great intellect though some mistakingly believe so. What I do possess (in my humble opinion) is a flexible, curious mind. I easily make connections across ideas that others might not. I see relationships among diverse phenomena that seem to escape others.

Perhaps these attributes, or blessings (?), would have predetermined what I would have become as an adult. Still, I suspect the serendipity that brought me to Clark University toward the start of the tumultuous 1960s was fortuitous indeed. I thank the fates for my good fortune.

I indeed was blessed. The greatest gift of any society is to permit, no encourage, its youth to think critically and independently. For all America’s faults back then, and we had just escaped the tentacles of McCarthyism in that period, I was able to refine my analytical and cognitive talents, such as they are.

It is that very blessing which our very own despot, Donald Trump, wishes to obliterate with his attacks on education, science, and our public data infrastructures. No one can control a people who can think for themselves. While the media currently may obsess about the Epstein files, the pecadillos of males are stale and unimportant news. Attempting to somehow disrupt both our access to objective information and our capabilities to critically process such would prove a tragedy from which any recovery would be long and uncertain.

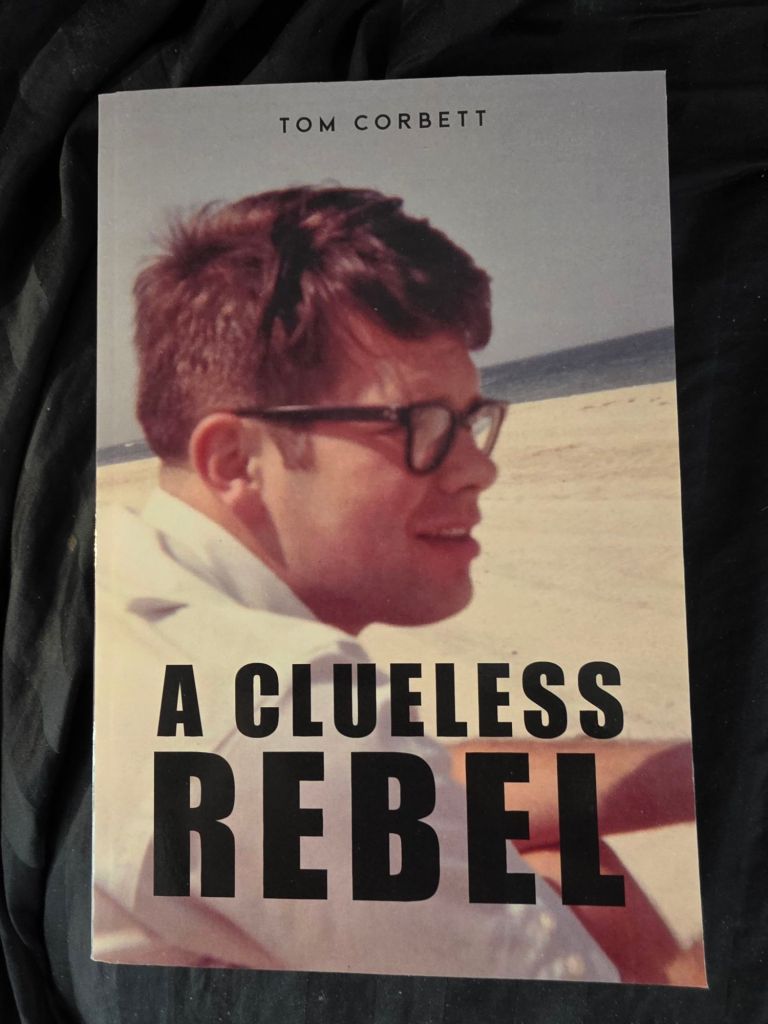

I’m arriving at a revelation. A very good friend recently shared an insight about my blogs. While she enjoys them, according to her, she finds them excruciatingly long. She’s correct. I always start with good intentions (keep it short, stupid) but I suffer from a terrible affliction … diarrhea of the brain. Thoughts just keep pouring forth. I had one thought for a story a number of years back and it wound up as a trilogy barely contained within three fat volumes.

So, I will stop here. The whole story is included in my memoir (below). But keep tuned, the abridged version just might follow in future blogs.