The denoument of English poet John Donne’s iconic poem on the significance of death goes like this:

Each man’s death diminishes me,

For I am involved in mankind.

Therefore, send not to know

for whom the bell tolls,

It tolls for thee.

Strip away the heightened language, Donne’s words speak a simple truth. We are all connected in obvious and less obvious ways. One person’s passing ripples through families and communities in ways both incontrovertible and incalculable. The same might be said for the institutions we create.

Two recent incidents remind me of this elegant concept … one at the institutional level and the other at a more personal level. First, I got a message that Elon Musk’s DOGE team apparently visited the National Peace Corps office in Washington last week. For many federal programs, such visits signal an imminent programmatic death knell, or nearly so in many instances. The second was a message that a fellow volunteer, Jerry, was near death after a lengthy battle with cancer.

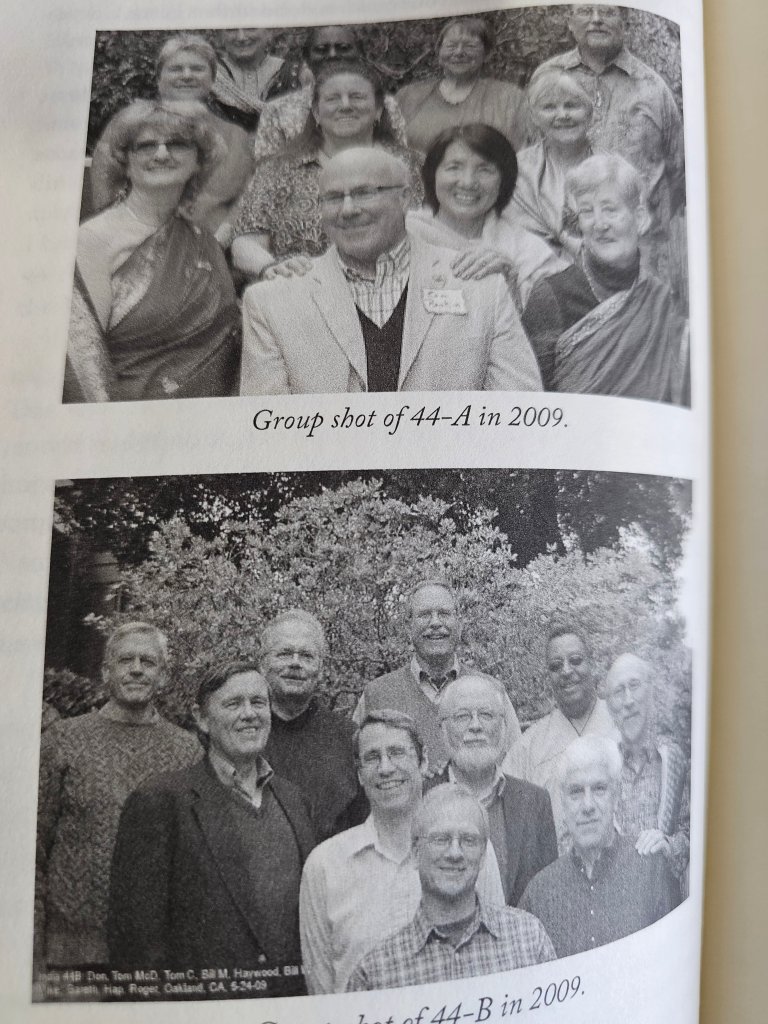

He and I were members of India-44 B, young men and women who, being inspired by John Kennedy’s words to ‘do something for our country,’ spent up to three years as Peace Corps volunteers. We served in hot and remote rural villages in Rajasthan and Maharashtra doing our best to improve public health or advance agricultural development.

Our overseas service was challenging to say the least. We faced disease, isolation, torpid heat, cultural frictions, and the embarrassment of working in technical areas that we had barely mastered. Hidden amidst the debris of self-doubt and second-guessing might lie the real reason we persisted in our mission on the other side of the world. For all our deficiencies and frailties, we showed the people of India a different kind of America and Americans. From movies and the media, they saw a society ridden with violence and exploitation, a people who too often employed power and arrogance to get what they wanted no matter the cost to others. That was the aggressive America and the ugly Americans.

In contrast, here were some Americans who lived among them, simply and without much pretense. Here were Americans who shared their lives and difficulties at the rawest levels. Here were Americans who tried to help, without apparent gain or advantage. If we left only a single contribution as volunteers, it might well have been a more balanced and favorable image of who we were as human beings with the mask of cultural superiority stripped away and discarded.

In doing that, we opened ourselves to new experiences and challenges barely perceived at the beginning of our journey. Our tenure on the other side of the world remained a time out of time. In the end, we experienced humor, doubt, success, loneliness, connection, some fear, embarrassment, understanding, and bewilderment. We endured a kaleidoscope of sensory and emotional assaults that it might take others a lifetime to accumulate. But, to a person, no matter how difficult the struggle, we felt that we emerged as better human beings, or at least different. Perhaps that was all we could expect. Perhaps that was enough.

As many know, the Peace Corps had a rather accidental birth. Presidential candidate John F. Kennedy landed in Ann Arbor in the middle of an October night in 1960. He was shocked to find some 10,000 yet waiting for his arrival, mostly students. Despite weariness from a just finished debate with Richard Nixon (in which the Vice President accused Democrats of being the war party), Kennedy spontaneously sought to strike a different tone in his remarks. He harkened back to some unformed thoughts he had been considering:

How many of you who are going to be doctors are willing to spend your days in Ghana? How many of you are willing to work in the Foreign Service and spend your life traveling around the world? On your willingness to do that – not merely to serve one year or two in (military) service – but your willingness to contribute part of your life to this country, I think will depend the answer whether our society can compete.

What happened over the next few weeks is the stuff of legend. Rumors of a new volunteer program flashed across college campuses even in those pre-internet days … a program that did not exist. The Kennedy campaign was flooded with queries about this new and exciting voluteer initiative. Kennedy’s simple questions that late night lit a spark under a restless generation, those on the verge of adulthood seeking a new world overall and a new role in their personal lives. So many in that moment and from that generation desired to make some positive contribution to what they saw as a possible brighter future.

Responding to a demand that refused to be extinguished, Kennedy created the Peace Corps by executive order on March 1, 1961. Since then, close to 230,000 Americans of all ages have completed tours across the globe. In 1966, when we started our long training as college juniors, over 15,500 volunteers would be serving in some 46 countries while tens of thousands of all ages, but mostly recent college graduates, would seek to serve. A half century after its creation, some 13,500 applicants would compete for 4,000 available slots.

A young man named Jerry grew up in Evanston, Illinois. As he approached completing college, he and others (like me) applied for a Peace Corps program that admitted college juniors into an experimental program that integrated training for a difficult tour of foreign service with their final college year. That would be our group … India-44.

I recall Jerry being extremely bright and imbued with a deep interest in philosophical issues, including a passion for social justice. He fully embodied the spirit of the times. He did not finish his tour, running afoul of medical issues that necessitated an early return to the States. Disease was one danger we all faced, and from which a number of us suffered. It later became apparent, however, that his desire to somehow contribute never flagged.

A while back, I became aware of a blog he created called Feathers of Hope. In it, he argued that we needed to resist our nation’s slow descent into autocratic rule and hard-right ideologies. He fought to give his readers hope as well as specific and well-considered actions through which the rising tide of Fascism might be reversed. As I read his blogs, I marveled at his eloquence and his tenacity. It was clear that the inner fires that prompted his service in India had never been extinguished.

And that was true of virtually all of those with whom I seved. They went on to exemplary lives of service to others and to society. An extraordinary number would earn graduate degrees from our best universities before embarking on highly successful careers. One cannot measure what our Peace Corps service might have contributed to this remarkable record of achievement, but one cannot discount that the input was substantive.

And then, last week, I received a notice that this would be his last blog. It was a brief message … mostly noting that Jerry was in the final stages of a battle with stage 4 cancer. He had never mentioned it. Perhaps that was to be expected. His personal struggles were of little consequence when pitted against our national peril. He can be assured of one fact, however. His spirit will endure … through the words he left to others and his undying devotion to what he believed was good and right.

These thoughts bring me back to why Peace Corps has been important and successful. Ultimately, it was the quality and sacrifice of the 200,000 plus individuals who, over the past half century, gave part of their lives to the simple notion that sacrifice and giving of oneself is a good and decent thing to do. It was never easy, nor does it always turn out as anticipated or like the feel-good ending of the movie Slum Dog Millionaire. Yet, if given the choice, we of India-44 likely would do it all over again.

Undoubtedly, we are better human beings for the experience. Perhaps more than that, we belonged to something special. We were, in fact, a band of brothers and sisters, with a connection that was forged half way around the world a lifetime ago. And yet, those bonds, that sense of sacrifice and commitment, endures to this day.

In those hopeful days, Richard Goodwin, an iconic speech writer for JFK, LBJ, and RFK (and who briefly worked with Sargent Schriver in the early Peace Corp days) penned the following:

Peace Corps touches on the profoundest motives of young people … that idealism, high aspirations, and ideological convictions are not inconsistent with the most practical, rigorous, and efficient of programs. [And that] every one of you will ultimately be judged – will ultimately judge himself – on the effort he has contributed to the building of a new world society.

If we do begin to hear the bell tolling for the Peace Corps, the sound will signal the passing of a noble experiment first heard in the heady days of the early 1960s. Back then, despite the rumblings of war in Southeast Asia and discontent with legal apartheid at home, we were a nation that dared to hope. We had big dreams for the future. If the bell does toll, it will foretell the sad passing of those grand aspirations. It will note the woeful sigh of a people too willing to accept small dreams and selfish aspirations.

These days I weep for many things … for Jerry, for the possible loss of this iconic program in which we both served and, lastly, for the passing of any sense of hope and idealism that once lit a sense of anticipation and belief in our youth. If we bequeeth anything to the next generation, it should be that … an insatiable desire to create a better world.