I am struck by the naivete of those who think doing public policy is easy. I spent my professional life in the public arena (pursuing poverty, welfare, and human service challenges). Believe me, these are complex, difficult nuts to crack. Yes, technical quests (e.g., putting a man on the moon, for example) we’re amazingly complex but eminently doable with sufficient treasure and effort. Social policy challenges, like the kind that kept me up at nights during my career as an academic and policy wonk, often fell into the category of wicked problems.

Just what are these wicked problems? They are public issues where the initial question might be ill-defined or ambiguous, where the theoretical basis for analyzing the issue is uncertain, where there is no consensus on the end points or goals, and where the available data and research are open to various interpretation. Good luck with that. I could explain how the vigorous welfare reform debates of the 80s and 90s (when it was a front-burner national question) were a poster child for a wicked issue, but that would demand a long dissertation.

Instead, I was thinking of something simple … a question on which I recently ruminated in my hyper-active mind. How do we think about fairness in our tax system? I bet each of us has said, publicly or internally, we’ll, that’s not fair. So, what is fair, what’s not?

Let us say you were put in charge of the nation’s tax system. Your mandate was to come up with a fair way of paying the country’s bills. Let’s briefly look at a few options for doing so:

A FLAT FEE … in this approach, every adult would pay the same in taxes no matter their income. You would divide the annual budget by the numbers of adults (or tax units) and arrive at a tax bill for each person (or family). This approach is simple and has a prima–facie look of being fair. You could argue that everyone gets a roughly equal benefit from public goods, so all should contribute equally. Of course, many would be forking over all their earnings while others could meet their obligations with pocket change. Still, some would argue that no one should pay more if they use a roughly equivalent value of the public good. And others would justifiably argue that some benefit from public goods more than others, though spirited arguments would surely follow that assertion.

A REGRESSIVE TAX APPROACH … In this approach, those with more pay less. This sounds unfair on the surface. Still, it happens and more than you realize. Sometimes, the very character of a tax is regressive even if it doesn’t appear so on first glance. A sales tax or a VAT (value added tax) can impact those along the income distribution disproportionately. For example, a tax on food hits the poor more since they spend more on food than the rich, and food is a non-fungible good (you can’t go without food, at least not for long).

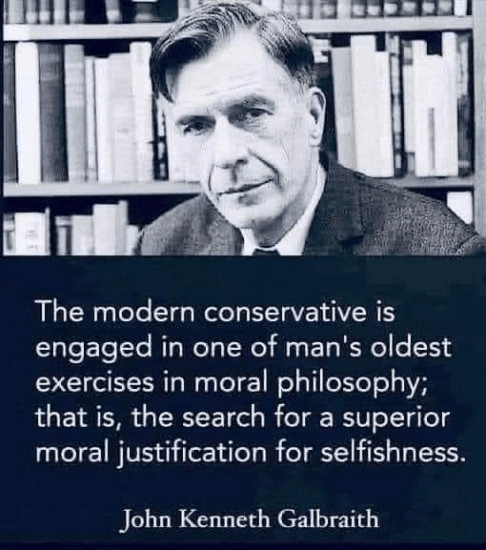

There are many variants on this theme. Sometimes, regressivity is a function of power. In the U.S., the tax system has become increasingly regressive both overtly and on purpose … more or less since the Reagan years. Why? Wealth buys power! And many working class folk vote against their own self-interest in this regard, a reality I yet struggle to understand. It is why Warren Buffet has pointed out the absurdity that he pays proportionally less in taxes than his secretary.

A FLAT TAX … this is similar to a flat fee but differs in one important respect. Rather than imposing a flat amount, every tax filing unit would be subject to the same tax rate. That sounds fair, being less regressive than the flat fee approach. Let’s say everyone would pay 20 percent. The rich would pay more in absolute dollars but at the same rate as their poorer fellow citizens. And yet, think about this for a moment? The average or flat rate would need to be higher for those at the bottom of the pyramid to raise enough money to pay the bills. Is that fair? After all, 20 percent of a $million bucks is $200,000, while 20 percent of $10,000 is $2,000. Should the rich person feel aggrieved? He or she often does.

A PROGRESSIVE TAX … A progressive approach to taxes results in those with a greater ability to pay actually contributing more. That sounds fair on the surface, though the rich have long squeeled in horror at the very prospect. They probably had a point when the top tax rate hovered at 90 percent for top earners after WWII. Yet, that progressivity enabled the nation to pay down the war debt, stabilize post-war Europe, invest in education (e.g., the G.I. Bill) and infrastructure, and create a robust and prosperous middle class. The conservative wing usually argues that high tax rates dampen risk-taking and innovation. Worst of all, it penalized success … oh, the horror. Even if there are rates at which work and investment suffer, what are they? Top rates of less than 40 percent have not demonstrably lessened the economic engine in the U.S. Yet, conservatives argue for further cuts, even as our public goods suffer while private incomes and wealth soar to unheard of heights.

A NEUTRAL SYSTEM … This principle touches less on the mechanics of raising revenue than on the overall purpose of the system. According to some, taxes should only be levied to pay public obligations and not for other purposes, no matter how worthy. I ran into this issue while working on a welfare reform scheme for Wisconsin. We looked at ways the state tax system could be made pro-poor (by the way, this work did lead to a state level earned income tax credit). One economics colleague questioned this quest of ours. At that time, he was working on tax reform in the state and had been arguing for a system that did not try to remedy other ills, even noble ones like poverty. If anything, we have looked to the tax system for solutions to many problems. While often a noble aspiration, many distortions and inefficiencies can be introduced. Or, as practices of the dismal science oft say, there is no free lunch.

I’ve only touched on a few principles and approaches in the tax system that impact the perception of fairness. No matter what approach you adopt, someone (some group) will argue you are not being fair. No matter how careful you are, there will be collateral damage and unintended consequences. They cannot be avoided. In truth, not all of them can even be identified in advance. And the worst impediment of all is the zero-sum game aspect of doing policy. There are few real win-win scenarios. That’s the bitter realty of the policy game. Yet, as I used to tell my students … you will not find a more frustrating and challenging professional avenue to pursue in the future, nor a more rewarding one.

One last thought! Think about the current clown car in Washington. They have made doing policy very simple. How will a change impact ME, OR MY SMALL TRIBE. Nothing else matters. With that definition of fairness, all becomes rather simple. You really don’t need experts to make policy, just hyper-selfish assholes. And yet, appointing the most incompetent clowns to high office (a kakistocracy) scares the crap out of me. True, you can make policy choices simple, but then you can’t find policies that work, at least not well nor for the public at large. I mean, really! Would you choose your plumber to do open heart surgery on you?

In case you are wondering, I wouldn’t.