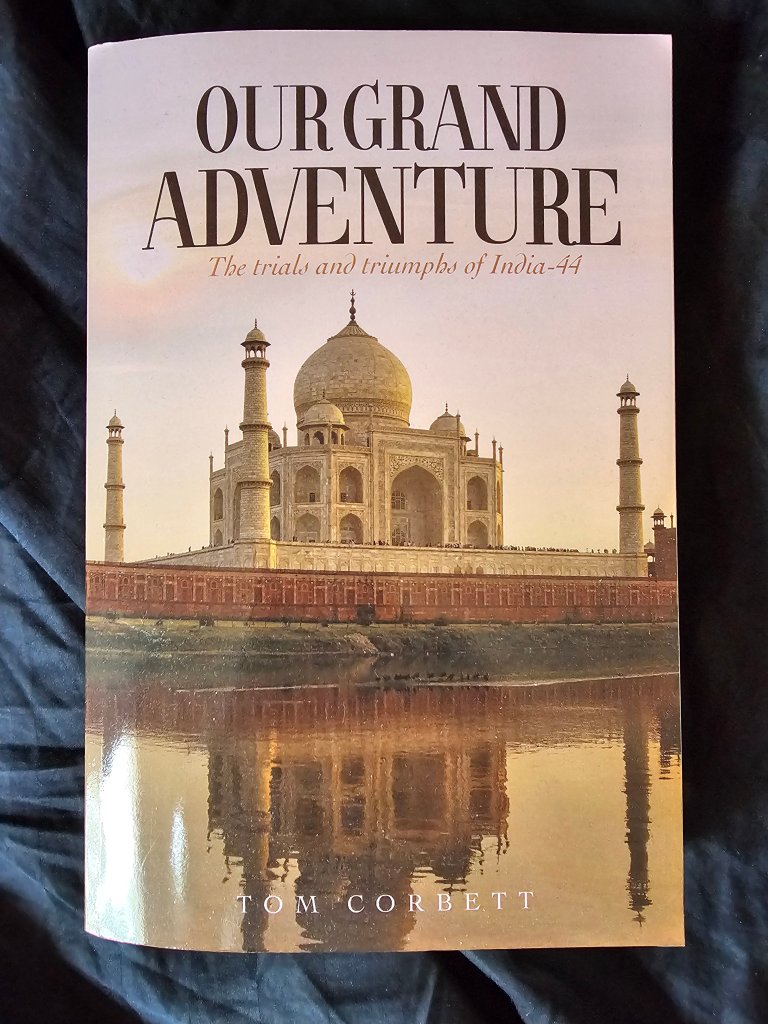

In June of 1966, close to 100 eager young college students gathered on the campus of the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. They were part of an experimental Peace Corps program that would expose them to an enhanced preparation regimen. These wanna-be volunteers would tackle a rigorous training ordeal that summer, return to finish their degrees, then be subject to more preparation the following summer before heading to India for two years. Many, actually most, would never make it. Some would be asked to leave. Others self-selected out during training. Still others withered in the challenges offered by India or succumbed to illness or disease. By July of 1969, at the end of our tour in one of Peace Corp’s most challenging environments, around two dozen tested volunteers would finish up their service. For these survivors, it was to be a Grand Adventure. (Check out the book below for the full story.)

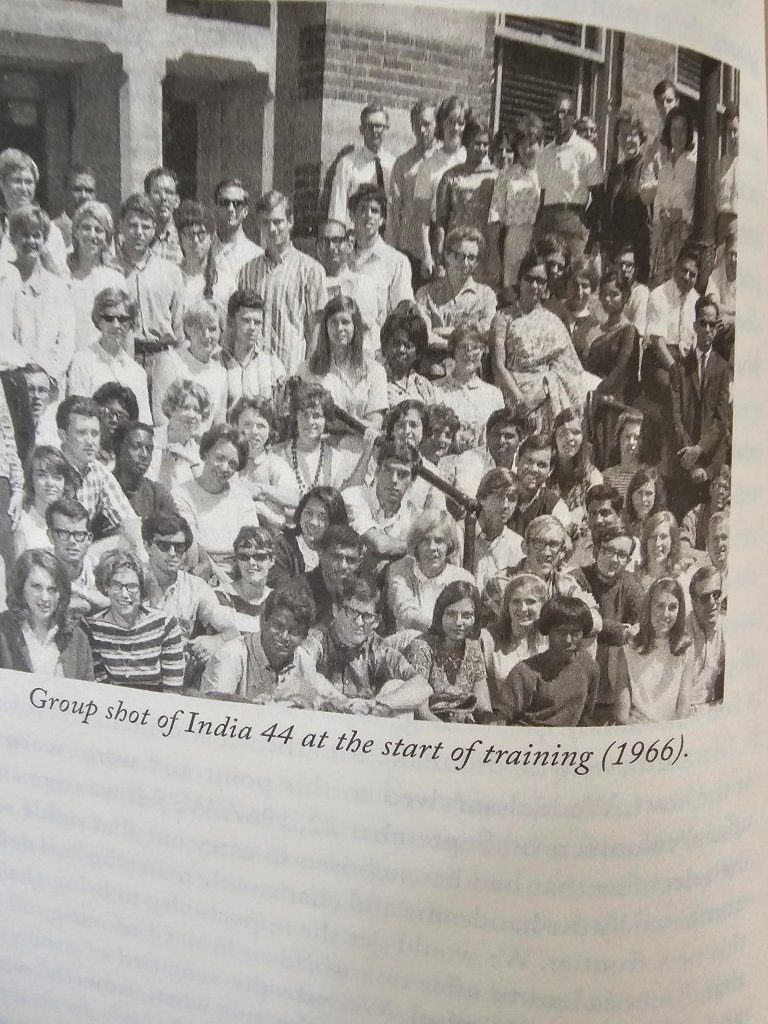

In the picture below is a partial shot of the young and eager college kids who signed up to spend two years in far off India. Little did they know what awaited them. If you have any interest, I am the geeky-looking guy with glasses in the second row on the far left. As I look back at these faces, I am reminded of how different the world was back then. This all happened when the very concept of overseas volunteering was still fresh and a largely unknown venture. Peace Corps, as a concept, was yet evolving through trial and error. Those early years would later be called the wild west era of the program.

There was a sense of institutionalized naivete that permeated that early program. It was assumed that smart American kids could be recruited off college campuses, given some training, and then dropped into remote sites without any resources other than their wits and good intentions. Oddly enough, in hindsight, officials actually assumed we kids actually could change the world. Some of us did … a little at least. But any small accomplishments were accompanied by frustration, disappointment, and often a sense of personal failure. India, for many reasons, was widely known to be one of the most difficult Peace Corps sites. Of course, we did not know that on the day this photo was shot.

This really was a special time in many ways. America was in the midst of such dramatic change. The conformist, conventional 50s had begun to crack open in the early part of the 1960s. The Civil Rights movement, with scenes of Blacks being persecuted for seeking an end to racial apartheid, was followed by Kennedy’s assassination and then the escalation of a far-off conflict in Southeast Asia. Such shocks drove many of us out of our personal torpor.

While I was quite political by the time this photo was snapped, many of the others undoubtedly were at the onset of profound personal changes. I was well along in my own transformational journey. Just three or so years earlier, I had been studying for the Catholic Priesthood (a foreign missionary order) after being raised in a conservative working class environment where independent thinking was frowned upon and divisive prejudicial attitudes the norm. God and country were paramount. Not surprisingly, I entered college as a product of my cultural cocoon. Change did not take long. By 1966, I was a veteran of antiwar marches who led what amounted to the leftist organization on my campus. I even joined the far-left Students for a Democratic Society (SDS), at least before it went over the radical edge.

Each of those kids pictured above had their own stories. Many (like me) were first-generation college students. They benefitted from a booming economy and a virtual explosion of new opportunities. A number went to the best schools … Berkeley, Columbia, Yale, and so forth, virtually all on scholarships or with easily accessible financial assistance. The costs of higher education in that period were laughably cheap. I could easily afford a private college with work, scholarships, and loans that were not back-braking. Others came from dirt poor backgrounds like share-cropping families who would make their ways successfully into mainstream society. As I look back, the talent found in this group was amazing … the accomplishments of the ones I know about have been astounding. Among the group survivors, it would be impossible to randomly select such a talented and accomplished group.

Many of us talk about the 60s with a kind of hushed reverance. In truth, it was a special moment in time. Not only did African -Americans wrest a degree of dignity from a reluctant majority, but several other ‘rights’ movements emerged … for women, for migrant workers and Latinos, for Native Americans, and for the disabled (along with movements for the environment and nuclear disarmament, etc.). The young questioned our military adventures abroad. Our national government declared a war-on-poverty. The arts went through an explosion of innovation. Everything was questioned. Most importantly, the search for a fair and just society was a-foot. Many in this pic traced their decision to apply to PC back to President John Kennedy (JFK) and his iconic challenge … ask not what your country can do for you, ask what you can do for your country.

The cultural zeitgeist back then was decidedly different. When college students were asked what was most important to them, developing a personal philosophy topped the list. Making money was much lower down. Some one-third of Yale law students tried to volunteer for crusader Ralph Nader’s consumer interest organization. The SDS organization I mentioned above only declined into nihilistic self-destruction in later years. It started out as a few University Of Michigan students sought a more meaningful future (see the Port Huron Statement). They were searching for a just cause about which to structure their futures.

That search for larger meaning is reflected in the early response to the Peace Corps concept. As I’ve noted elsewhere, the concept was first publicly presented by Candidate JFK during a late night stop in Michigan after a TV debate with his opponent… Richard M. Nixon. Dick had gotten under JFK’s skin by asserting that the Dems had been the war party while the GOP favored peace. In response, Jack stewed in the plane ride to his first post-debate stop, Ann Arbor Michigan. He challenged the mostly student crowd (it was near midnight when he landed) to be willing to sacrifice a year or two abroad to make the world a better place. It was a throw-away line at best, totally off-the-cuff.

Jack could never have imagined what happened next. That suggestion roared through the imaginations of the youth in that audience. In those days of primitive communications, word spread of this new volunteer opportunity … by posters on college kiosks, via early telephones, and through face to face conversations. Still, the word spread like wildfire from campus to campus. Even while the campaign was in full throttle, Kennedy’s staff was overwhelmed with requests from students and young people trying to sign up for this new program that did not exist. The response was so overwhelming that, when elected, JFK felt compelled to create the Peace Corps by executive order on March 1, 1961.

That enthusiasm had not abated when I sent in my application in late 1965. The D.C. central staff were still being inundated with applications, way more than they could possibly accept. The youth of that era (my era), while making many poor decisions in retrospect, were generally driven by the better angels of their natures. Many truly wanted to leave the world in a better place. Those were the prime sentiments that drove me. That was why I tried to become a missionary priest, why I worked with poor and disadvantaged kids, and why I became an orderly on the 11-7 shift in a large, urban hospital. Even during my college years, I wanted to make a difference.

Sure, we lived during a golden economic era. Poverty and inequality were falling. The possibilities, even for relatively poor working-class youth like myself, were getting better. While we worried about nuclear incineration for sure, we somehow believed a better world was in the offing. We simply had to ensure that it happened.

If you had been there that day in June of 1966, you would have felt that faith, that optimism. I taught college students for many years. Sure, many impressed me with their idealism, intelligence, and commitment. But nothing matched those heady days when we were eager to set off to the ‘other side of the world‘ to make things just a little better. During that era, there existed a philosophical leitmotif that was quite special. Moreover, I suspect we were among the best of that unique generation.

I will pick up this theme in future blogs. Stay tuned!