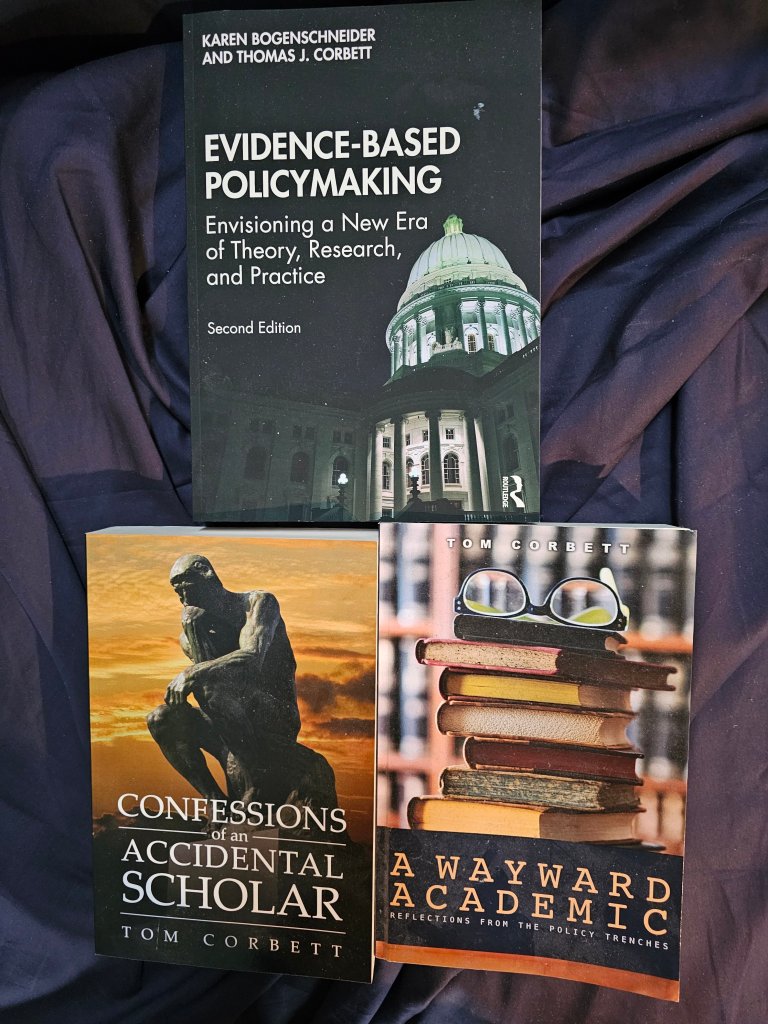

I’m moved to add a bit more to yesterday’s post, though I’m not totally convinced this is merely an addendum to what I previously offered. No matter, this touches on an issue I have dwelt on for many years. In fact, I’ve covered such in several books (see pic below).

Last time I focused on the faith versus science dichotomy, a chasm that goes back at least to Galileo if not much earlier. Yet, that societal tension might well be overly simplistic. For one thing, faith can provide a good deal of emotional comfort as long as it is kept in perspective. That is, don’t push your beliefs on others and don’t substitute your faith for constitutional protections or sensible laws or scientific facts.

On the other hand, science also has an element of faith. We put our trust in those who have mastered the scientific method and technologies that few of us understand. Thus, when scientists announce they have measured the Higgs Boson, a critical sub particle first hypothesized mathematically a number of decades ago, the reality of this discovery remains a matter of trust for us mere mortals. We will never see it, feel it, or have any contact with this ‘thing.’ Yet, some of us share in the excitement of its discovery. After all, a collection of cooperating countries spent billions erecting the hadron collider, a miraculous piece of technology that spans two countries, just to find (among other things) some proof that this mysterious thing exists.

There is another gap beyond faith and reason that deserves mention. There is a chasm between what I call knowledge producers and knowledge consumers. This is another oversimplification that separates scholars (and scientists) who search for mostly new knowledge from those who purportedly employ that knowledge for the betterment (we hope) of society. Naturally, members on both sides of the divide create and use knowledge but apportioning these distinct roles has some face validity.

What separates knowledge producers from users are culturally embedded barriers that hinder communication. Each tribe has different aspirations, goals, language, operating styles and institutional rewards that render collaboration difficult to say the least. My colleague, Karen Bogenscneider, and I called it cultural dissonance.

I’ve written much on this topic (see above publications) so won’t belabor it here. However, during my long career in academia (though I considered myself more of a fake academic), I was most dismayed at how provincial and narrow my colleagues remained. Most remained within the confines of a scholarly prison. The peer reviewed literature was the source of all knowledge, their disciplinary peers remained the only audience worth their time, and publication in select disciplinary journals their only worthwhile products. Given a choice of curing cancer or publishing an article in a top-rated journal, most of my peers would not hesitate to choose the latter.

I would laugh when I came across university propaganda suggesting that faculty would be assessed on research, teaching, and public service. Right! In my experience, teaching only counted at the margins and only if you didn’t put too much effort into it. If you did, you were not a serious scholar. Nor did all research count, only that which found its way into accepted academic journals. And public service, forget about it. Doing good for society was always seen in the negative. Clearly, you were wasting your time tackling social issues no matter what fine language was included in University mission statements.

Aside from restating my age-old gripes about the myopic academic culture, I do have a point to make. We are way too tribal. Some tribes are obvious … the politically left and right, the wealthy versus those struggling, black and white, urban versus rural, the list could go on. Those believing in science versus mere faith/personal experience is another social divide. And within those leaning toward reason, we have the tribe of knowledge producers and consumers. Too many ways of separating us and keeping us apart. At the same time, too few visionary thinkers engaging in lateral thinking to bring us together.

In the end, we need more cultural bridgers of all kinds. We need those who can walk across the divides, who can translate the distinct languages, and who can forge new cross-cultural relationships. The future will be built on cooperation and collaboration. Those who can make that happen will be the heroes of tomorrow.

One response to “Conundrum # 4 (continued).”

Well done.

LikeLike