The picture above was my college graduation shot. I was quite pensive, even serious. I could easily have been mistaken for a business major heading for a Wall Street career. As discussed below, nothing was further from the truth. It might be more accurate to describe me as a quiet, perhaps clueless, rebel in training.

Most likely, I was reflecting on all the changes that had taken place since I had left the seminary three years earlier. Or perhaps I was anticipating the further changes I would experience in India as a Peace Corp volunteer. The metamorphosis I experienced in those so-called transional years was fundamental and profound. I emerged from a cocoon embracing, perhaps suffocating within, a Catholic and conservative working class culture to become someone with an insatiable curiosity about the world and a desire to change things.

I

A quick note on my seminary experience (above, I am with my seminary roomates … both named Peter). A general and likely religious inspired desire to do good led me to the seminary. I joined a foreign missionary group partly because I wanted to help the less fortunate in some material manner. What better way to sate that pervasive Catholic guilt and fulfill Christ’s core message. Go forth and do good!

Eventually, the obvious dawned even on a slow learner like me. Really believing in God was a prerequisite for the job. That, it finally hit me, was a job requirement one could not fake, at least not easily nor for long. Besides, there just might be more appropriate ways to save the world, like this new Peace Corps thing. But that would have to wait until after college.

I returned home in the fall of 1963. I found out that Holy Cross, the Catholic College I would have attended straight out of HS would not accept spring semester applicants. I’d have to wait until the fall. That was just the excuse I needed to apply to Clark University, also located in my hometown (attending school out of town was financially infeasible). In truth, I was intrigued by this place known within the local Catholic community as a den of atheists and Communists. I had not met any of these derelicts to date.

Serendipity was undoubtedly at play here. Clark was a small, liberal arts school with an interesting history. It was founded as the 2nd Graduate school in the U.S. (after John’s Hopkins). When Sigmund Freud lectured in the U S., he came to Clark (that is a statue to him above.) Later, Robert Goddard (known as the father of the space age) developed the liquid fuel rocket to further his dream of space exploration. Over time, Clark settled into a niche as a very good, though not necessarily a top-tier school. I wouldn’t have gotten in if it were, having been a middling student at best early on.

Suddenly, I was thrust into a perfect environment. It was small, intimate, with an atmosphere that invited risk-taking and free inquiry. I found like-minded intellectual adventurers (including several graduate students) who joined me as I explored the boundaries of my existing world view. We would spend hours (sometimes pulling all nighters) debating the issues of the day as we tore apart the presumptions with which we entered school and painfully erected our new world views and moral compasses. In the end, I had undergone a radical change. I have little doubt that I owe much of whom I am today to my days at Clark. Being a child of the turbulent and activist 1960s helped a bit as well.

As I approached graduation, I went back to the same impulses that had drawn me into the seminary after high school. Now, however, I had a better sense of who I was. I would do a kind of missionary work but with a more secular mission … the Peace Corps.

After a long and arduous training regimen, I would soon be off to India as an agricultural specialist. Don’t ask, it was not one of the better schemes Peace Corps launched in those early days. Again, in hindsight, the botched character of the program may inadvertently have been a blessing.

I can’t fully share the PC experience here. I can not even come close. My small group that survived the training and early experiences in country went on to endure heat, isolation, cultural friction, various illnesses, confrontations with snakes and other creatures, and intense feelings of inadequacy. As smart as we were, we were expected to contribute in technical areas in which we had little competence. Yet, failure could have significant consequences for those living at the margin

Over two years, I managed to start a number of ag projects using high- yield experimental seeds, start a home poultry project, help the local schools, and make a few good friends, among other things. But mostly, I had two years of solitude, time to reflect, to read voraciously, to write my own novel, to learn to appreciate diversity in this world, and to gain valuable insights into the importance of culture. I began to understand the pace of life, especially how others saw things. My world was not the only world. I eventually brought these last lessons with me into my subsequent careers as a policy wonk and an academic.

Many of us got together some 40 years after our return home in 1969 (see pic below). It was an emotional experience (the first reunion I ever attended). We realized how deeply we had been touched by that experience, including how many of us had felt like failures. Oddly enough, this was our first real opportunity to express and process feelings from four-plus decades ago.

But as I looked about at my now aging fellow volunteers, and as I listened to the shared stories, I realized how fortunate I had been during these formative years.I had met such talented and successful people, like the ones in that reunion room. Most had gone on to do amazing stuff, including garnering advanced degrees from the nation’s top schools.

And my story! I had gone from an intense religious encounter in a seminary to a college experience that, in addition to opening up new worlds for me, pushed me to fundamentally reorder my world view, and then on to a unique cultural experience that both tested me and exposed me to previously unimagined challenges. It was not always easy, but I had been fortunate indeed.

As I reached adulthood, I still did not know what I wanted from life, but I did know I would do it on my terms. I brought forth with me all the experiences and turmoil from my so-called transitional years … the introspection of my seminary experiences, the social activism and intellectual turmoil of a 1960s college experience, and an unforgettable cultural immersion in rural India. I was ready for anything.

In truth, I rather stumbled into a career through a series of unplanned events. It is better to be lucky than good since I never had a plan. At the end of several twists and turns, I had a masters degree and later a doctorate. Somehow, I wound up associated with the prestigious Institute for Research on Poverty at the University of Wisconsin. This was the pre-eminent academic based national think tank on social policy issues. It is the only such institute to receive federal support continuously from Johnson’s War On Poverty to the current day.

It was a special, and fortuitous, landing for me since I could pick and choose the issues I wanted to pursue. Personal freedom is one perquisite of an academic position I love dearly (there are less desirable aspects of academia). I also had an opportunity to pass on whatever I had to share with future generations of idealists interested in shaping the world. I loved teaching.

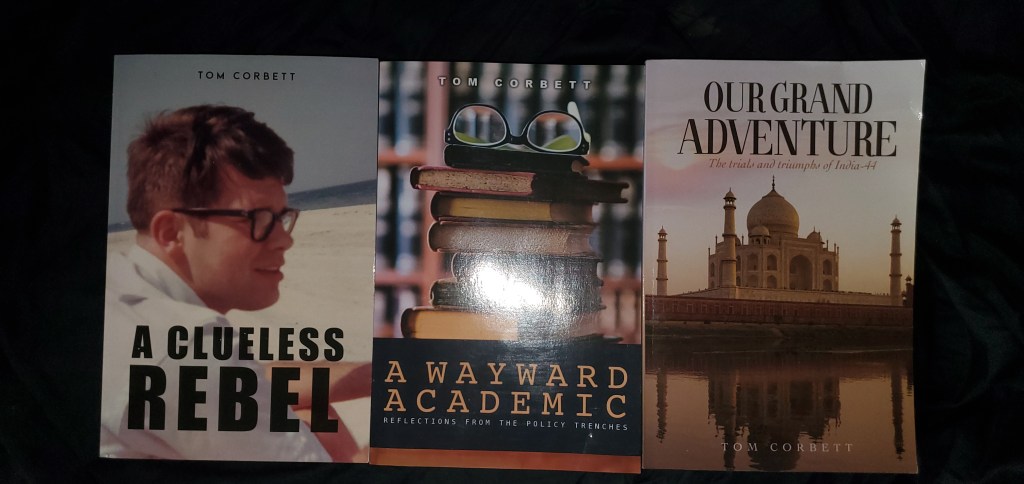

In A Wayward Academic: Reflections from the policy trenches, I describe my fascinating career where I had a front row seat to many of the hot policy issues that embroiled the nation from the 1970s through the start of the 21st century.

Being a free lance policy-wonk proved a perfect spot for a dilettante like me who had trouble focusing on a single issue, at least not for long. You might imagine that I wasn’t a conventional scholar or academic … they had to be extremely focused to be successful. But I could be insightful, clever, synergistic, and worked well with diverse audiences.

Best if all, helping run the premier research entity on poverty and welfare issues when they were front burner concerns opened so many doors to me. Perhaps my priceless experiences during those transitional years gave me a perspective and advantages others did not possess. It wasn’t any of the usual or conventional skills since I was the kid who barely passed high school algebra. Yet, I still found a seat at the policy tables.

When I stepped down as Associate Director of the Institute for Research on Poverty at UW (and retired from teaching policy courses at the undergraduate and graduate levels), they threw a nice party for me. I told those assembled that I had been blessed. I managed to find a position where I basically flew around the country to work with the best and brightest on the nation’s most perplexing social issues. And best of all, I was paid to do this. Not bad for a hopeless working-class Catholic kid with no apparent skills whatsoever.

If this tour of my early years intrigues you, try my memoirs. A Clueless Rebel covers my early years in general with great humor. Our Grand Adventure: The trials and tribulations of India 44 covers my group’s Peace Corps experiences. And A Wayward Academic: Reflections from the policy trenches covers my career as a policy wonk. It is also a cooks tour of U.S. policy from the ‘war on poverty’ to the ‘war on the poor.’