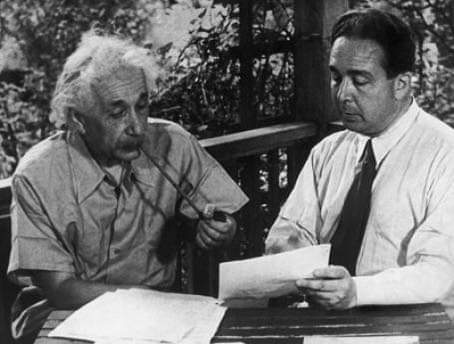

Earlier this month, way back in 1939, Leo Szilard visited Albert Einstein to convince him to sign a letter to be forwarded to President Franklin Delano Roosevelt. Szilard, a Hungarian born physicist, had conceived of the potential of nuclear fission earlier in that decade, though Einsteins work provded the basis for such intellectual breakthroughs. One consequence of their theoretical work was the potential for a weapon of fantastic destructive potential.

By 1939, it was more than apparent that the Nazis were on the road to war. In fact, when Szilard petitioned Einstein to join him in pushing the President to be aware of this new atomic age, the Polish invasion that made this a worldwide conflict was just days away. Szilard was particularly anxious to get Albert’s support since he was virtually the only egghead of sufficient public acclaim to possibly get Roosevelt’s attention.

Einstein, in fact, needed some persuading. He was, by instinct, a pacifist. He had been very critical of some of his academic colleagues who had helped the German government during WWI, especially in developing nerve gases and more destructive technologies for use in that conflict. He was torn by Szilards request.

In the end, he did sign on. We believe his rationale was understandable. Einstein was now at Princeton, having left Germany when the Nazis came to power. In fact, he was in the U.S. giving lectures when that happened. He was denied reentry and, after spending some time in England where he felt his life might not be safe from Nazi assassins. He soon migrated to the States but retained personal experiences of the depth of Nazi perfidy.

He, and most other top scientists, knew that Germany had many top brains available to them, brilliant men such as Werner Heisenberg and Wernher von Braun. They concluded that the Nazis might just get the jump on the allies in developing the next generation of super weapons. In fact, the Germans did develop ballistic missiles and jet planes, but too late in the war to do much good.

However, what if they beat the allies to the forces of nuclear fission? Of course, this is one of the core moral issues underlying the compelling and riveting movie … Oppenheimer. Scientists, even those morally opposed to war, felt they had no other choice. Robert Oppenheimer was a classic example of such an internal debate. He, including many of his colleagues, was trapped in what economists call a prisoner’s dilemma. Not knowing what the other side was capable of achieving, could they stand by and do nothing?

The other moral question was whether to use this new power or not. By the time it was realized that the atomic bomb was feasible, the overarching calculus had changed. By late 1944, those working on the bomb suspected, or began to believe, that Germany did not have the head start initially feared and was nowhere close to having a bomb. Their fears from a few years earlier were not to be realized.

Some considered delaying the culmination of their work, or at least demonstrating their concern by opposing their own creation in some fashion. However, their drive as scientists, along with the motivation inherent in being a part of the most exciting scientific enterprise of the 20th century, pushed them on. I believe that were some of the complex emotions brilliantly conveyed through this masterpiece of a movie.

When they saw the mushroom cloud on July 16 at the Trinity site in New Mexico, they fully appreciated the consequences of what they had done. Some remained enthusiastic, others immediately regretted their participation. Oppenheimer quoted an ancient Sanskrit text … I am Shiva, the destroyer of worlds. Einstein would later say that signing Szilards letter to Roosevelt was the biggest mistake of his life.

Then there was the decision to use the bomb. Once it existed, the scientists would lose control over its use. As depicted in the movie, Truman tells Oppenheimer that he dropped the bomb, not some egghead. But the scientists who came to regret their participation could not so easily forgive themselves, not totally.

So, how much guilt and remorse should they carry? How much guilt, if any, should Truman carry for actually using the weapon? These are all questions embedded in much moral ambiguity.

Can anyone blame the scientists who worked on the bomb for doing so given the information set available to them at the beginning of their work? If you thought the most evil regime imaginable might develop this awesome weapon, could you stand by and do nothing? Oh, I can think of rationales for taking that chance (on doing nothing), but they are not convincing even to me.

And Truman’s decision to use it. Think of his world in that moment. As allied forces got closer to the Japanese mainland, the ferocity of the fighting grew along with casualties. The two atomic bombs incurred sone 120,000 immediate deaths and thousands more later. The scenes of unimaginable suffering haunt some of us even today.

However, any conventional invasion of the mainland would have resulted in many times that number of casualties. The saturation bombings of Tokyo alone (to soften up the population prior to an invasion) would have resulted in many more deaths. That city was made mostly of wood for crying out loud. Just think about the horrors of allied bombings in Dresden and Hamburg that generated fire storms of unspeakable fury.

Many argued that using the bomb made it permissible to use it again in the future. Again, the movie touches on this brilliantly. As Oppenheimer argued, the only way to show the world how awful this weapon is demanded an actual demonstration or two. Yes, this might be a convenient rationale, and these examples might have had the opposite effect. However, the world has lived with this power for almost 80 years without using it again. Mutual destruction has proven an effective deterrent, though we have come so close to the apocalypse more than once.

Yes, we might have created a weapon so destructive that we cannot use it again. When we did use it, there might well have been fewer deaths and less destruction than we otherwise would have seen. We can never know for sure.

We have the benefit of hindsight. Perhaps that’s why I loved the movie so much. It put me in their shoes. What would I have done? What choices would I have made? Few of us are thrust into a situation where such monumental decisions are demanded. Few of us confront such existential choices of such enormity.

Thank God for that. They are not easy ones to make … not when you are in the center of the storm. I am thankful that I have been so irrelevant in life.

3 responses to “A Mistake … or Not?”

As it happens, I’m going to see the movie this afternoon. I can’t wait.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Tom,

I loved the movie too. It was so well done. Reading this makes me want to see it again.

Thanks for your thoughts on it. Loved this post.

Beth

>

LikeLike

I saw it twice, Beth. Very seldom do that. On the other hand, I went to see Barbie out of curiosity. Decent message but too fantastical for my tastes.

LikeLike