[Note: I was going to work on this some more but I had too many technical difficulties, so here it is as. Could be better.]

I zoomed with several of my old Peace Corps buddies the other day. The nominal reason for this cyber gathering was that one of our aging flock recently met with our Peace Corps training director who, as we realized at some point, was not much older than we were when he helped prepare us for our adventures in India. Now he is in his 80s while the rest of us are in our upper 70s. In some ways, our long ago a excursion to the other side of the world seemed like it happened yesterday. In other ways, it might have been from someone else’s life.

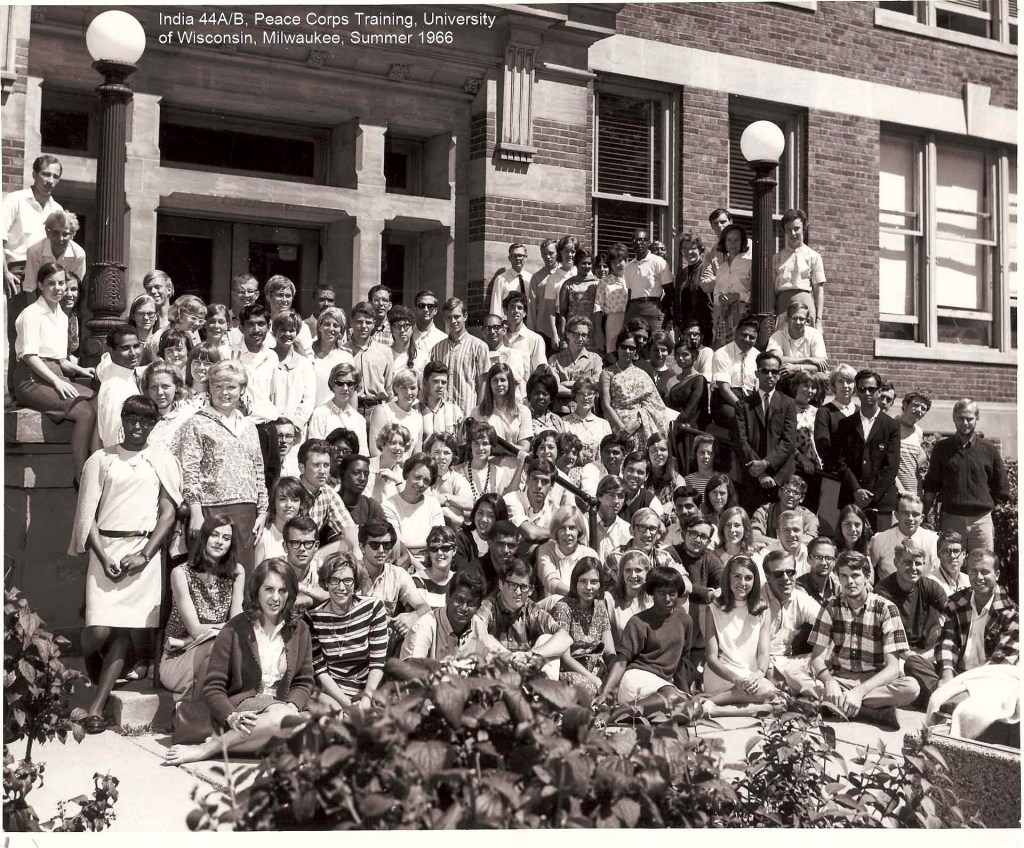

Let me say a few introductory things about the trials and tribulations of India-44. As the number suggests we were the 44th group to go to the sub-continent. We were all college kids, chosen in our junior years and given extensive training over two summers before being sent over upon graduation. All this happened during what has often been called the ‘wild west’ of Peace Corps service during the mid1960s when we started our service, or preparing for it at least. They hadn’t worked out all kinks yet and we were the guinea pigs for a number of innovations and experiments. But we were young, idealistic, and naive. Some of us thought it would be a great excursion into the unknown. Indeed it was.

Can you find me?

The training would be long and, in some ways, arduous. We started at the campus of the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee where we were immersed in language training, technical preparation, cultural awareness initiatives, physical trianing, and a whole bunch of tests and challenges to see if we were fit and likely to survive. We met again during our between semester break in our senior years before returning for more intensive preparation before being sent abroad for (guess what) more training.

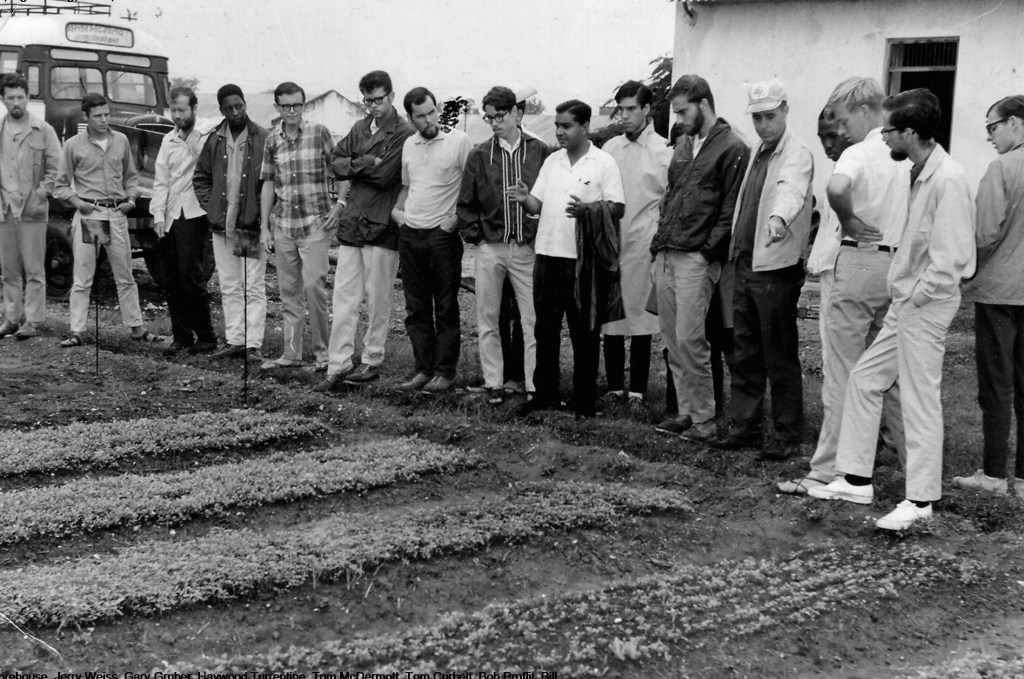

Amidst the on-campus lessons, I spent time on a Native American reservation in South Dakota (truly the end of the world) where we were exposed to a cross-cultural experience. The next summer I spent time on a farm just north of Madison in Waunakee Wisconsin where we lived in tents and tried to become farmers. I’m guessing the whole ordeal would have gone better if they had not changed the focus for India 44-B (my specific group) from poulty to agriculture. I am guessing the pic below is from our tenure on the farm. I’m the tall one in the middle and beginning to look a bit scruffy.

From a detailed journal kept by Mike Simonds (the young man on the left of the pic above), we were reminded of the grinding schedule. He lsited out several days of activities, classes, events that went from the crack of dawn to late in the evening.

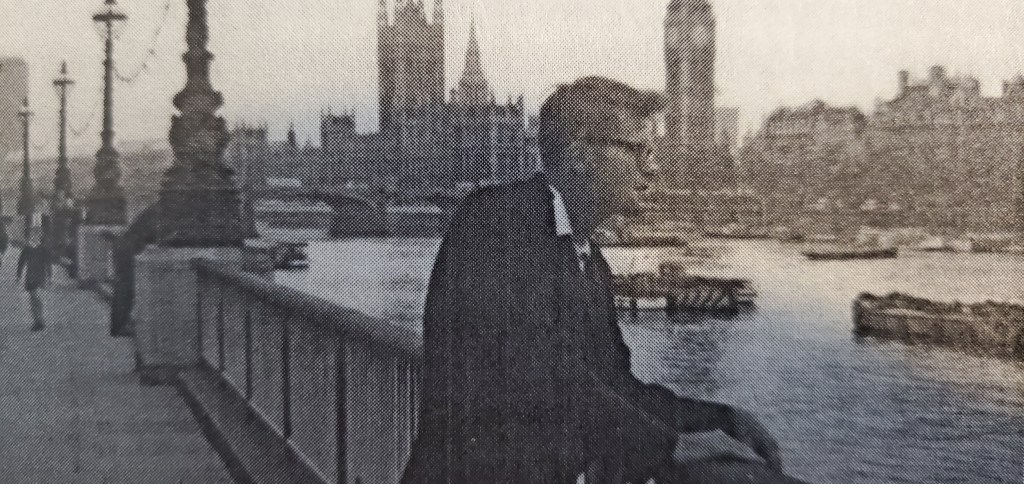

At every turn you wondered if the ax would fall. Someone would be brought in for a meeting and sent home. The choices were bizarre. How could they have kept me when others who appeared more talented and dedicated were sent packing. Still, in the summer of 1967, we were off to India. This is me, looking over the Thames during our a brief break in London. I wonder what was going through my mmind at this moment? Probably somehting like ‘what the hell have I gotten myself into.’

Of course, we then landed we did more training. Here are a bunch of us from 44-B (see below), the would be Ag experts now refining our skills (or perhaps realizing for the first time that many foods grow out of the ground and do not appear by magic in grocery stores. Despite the staff’s good intentions, you cannot turn college kids from the city into farmers in a few weeks. Well, they couldn’t turn me into one.

You might be asking what happened to the women. They were assigned to 44-A, a public health group that were to be stationed in Maharasthra, the adjacent province to our south where Mumbia (then Bombay) could be found. While we learned Hindi, they learned Maharati. We were sorry to be separated but I suspect they were thrilled to be safe from a bunch of testosterone laden young males. I know they were ecstatic to be away from me. I tended to drool a lot when around them.

Can you find me here?

There were some high moment before we were sent off to our sites. We played several basketball games against the local college kids (see pic below) whipping them soundly before they got ther revenge. For the last game (before a large crowd) they brought in a new team, either from the army or the local prison. These bruisers did a job on us to the delight of the cheering local onlookers. Every time I drove to the basket, I would get pummeled. Hard to make many shots when your hurling them toward the basket from 50 feet away. But we survived.

Even better, three of us were asked to join a team representing Udaipur (we were to be stationed in the vicinity of this lovely city in Rajasthan) in the all India tournament in Jaipur. Myself (lower extreme left), Bill Whitesell (next to me) and Hatwood Turrentine (4th from left) were selected to help bring basketaball glory to the area. What we didn’t know was that the other teams could really play the game. We were soundly defeated in our first game, then won a consolation game, before heading home in shame. But it was fun.

In September of 1967, those of us who survived were sworn in as Peace Corps volunteers. We had one last party at the Lake Palace before two years in the desert. The Lake Palace was a former playground of the local Maharaja situated in the middle of lake Pichola. It is now considered one of the most luxurious hotels on the world. A good deal of one James Bond movies used it as a site (Octopussy?). Two of my colleagues stayed there a decade ago and attested to its splendor. It was like the last feast before the slaughter, the final meal before the long walk to the ‘chair.’

I am on the left (glasses) talking to Usha (one of our language instructers) on the right. I, and a couple of others, actually got to know Amar (next to Usha) and her family quite well. We were invited to the Punjab to witness the marriage of her brother (a military officer), a lavish affair that went on for what seemed like days. Indian marriages (and celebrations there in general) can make ours look tame. Making such connections enriched the experience immensly.

Reality hit the next day when three of us boarded the back of a truck with our trunks and all out wordly goods and hurtled out of the Adravelli Hills into the desert to the south. We arrived here on a Sunday. No one greeted us. Here was the local Panchayit Samiti, the government development office and our new home. The town of Salumbar was about a mile further over the next hill. The third of our group was to be located even further from civilization, there was no way he could survive.

I yet remember hopping on my bike and cycling to find someone who might be in charge, which I did. Randy (my site partner) and I took one of the government houses (far right). No other government official lived there, preferring to live in town. I could go on about life here, which had its good and bad moment. We were really isolated, no electricity for 6 months and never running water. We relieved ourselves in a small, smelly room with a hole in the floor. That bodily function was not easy to negotiate on nights without moonlight.

The temps often were north of 110 drgees except in the brief winter and the monsoon season (when all type sof crawling and flying creatures came to life). I recall checking out a desk in our place and finding a scorpian looking at me. During the rainy season, you kept a lid (a book?) on your cup, only lifting it to take a sip, then covering it again. If you didn’t, you would be ingesting several bugs with your next swallow. It was not for the weak of heart. Still, we often spent the evenings on our roof, as the desert cooled and the most amazing field of stars were revealed to us. I have never since been so close to nature.

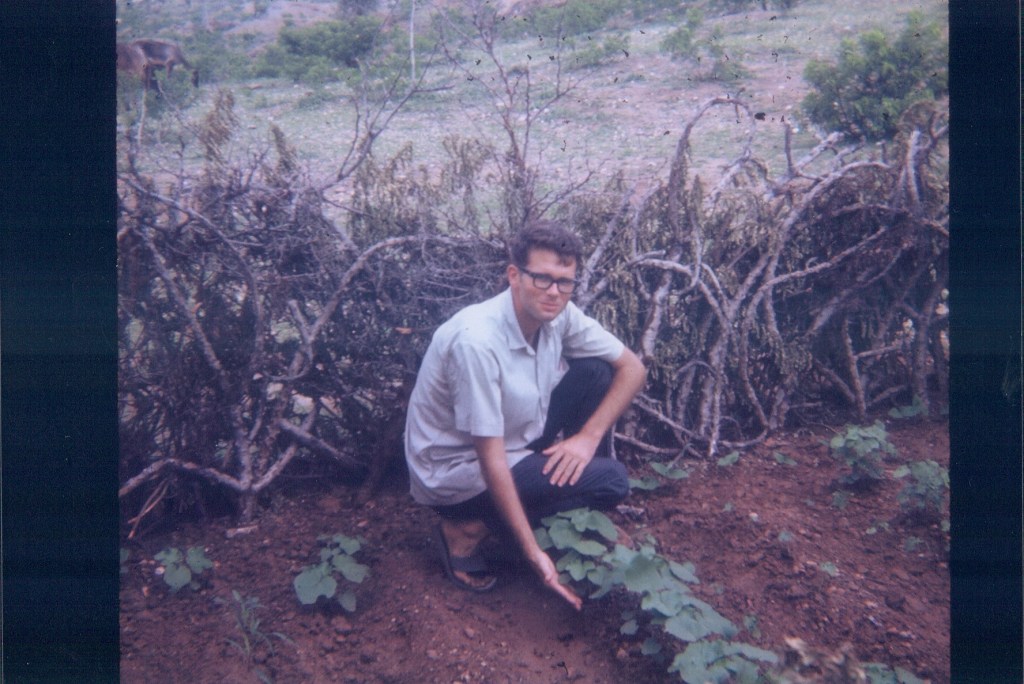

Most of us felt quite incompetent. What made that critical in a way is that most farmers were marginal. They had small plots that could yield just enough to get them to the next year. But we were there to motivate them to try new seeds and techniques. Fine, but these innovations required good practices performed at the right times. If things went wrong, and so much could, the poorer farmers would be in deperate straights and our guilt would be astronomical. So, we selected our guinea pigs carefully. Below is one demonstration plot we worked on as an example to the community. Looks good to me.

Still looking for things to occupy our time, we thought a poultry demo would be good. We built this ourselves (the ONLY thing I have ever built in my life) on our roof to keep predators away. I still recall the excitement when the first egg was laid. Success was measured in the smallest ways.

And we did a bunch of other small things. Here is a modest garden outside our remote place. Our protective wall (at my back) worked for a while but not forever. We lost the crop at some point when the local predators breached our defenses. But we knew our produce was edible. Oh well, A for effort.

Below is a street scene in Salumbar. We spent a good deal of time here, made a few friends, and became part of the community. This scene best captured how I felt about the place. It struck me as a throw back to Dodge City in the 1880s. I thought surely Matt Dillon would face off with a desperado at high noon. I still recall one day watching several men, riding camels down a street (probably this street). They had rifles slung over their shoulders and belts of ammunition. I thought, the James Gang come to town to rob the bank. No such excitement.

On another occasion, a group of Jain Saints visited to great local fanfare. Apparently, this entourage walked around India and it was a significant event if they made their way to your town. What I recall most was one Saint pulling all his bodily hair out as an exercise in self-mortification. I then realized why I had left the Church.

Meanwhile, our sisters in 44-A were laboring in villages to our south. Since I had worked in a hospital while in college I had hoped to get into the public health part of the program. Such was not to be. I considered appealing my assignment early on in training but feared rocking the boat.

In any case, here are two of the intrepid gals, Mary Jo and Carol, doing something medical in their site. Mary Jo (on the left) was a nurse and one of the few with actual and relevant skills. In the end, nothing bothered us more than the feeling we had little to offer. I seemed to recall that there were two rumors about why we were there. One option was that we were CIA spies but there was nothing to spy on here. The other was that we were there to learn agriculture so we could be farmers back home.

Despite all the doubts, probably more got done that we recall. There were demonstration plots, some schools were built with volunteer help, wells dug, and so much else like poultry initiatives. We did not change the world but we might have altered a few lives. That is enough in the end.

What you don’t forget are some of the connections that are made. Here are the three I mentioned above that the local Udaipur College boys chose to play on their basketball team in that ill-fated tournament (discussed above). There is Haywood on the left, me, and then Bill. We are at the Delhi home of Amar (pictured in the Lake Palace foto). We grew close to that family.

In some ways, the three of us represent the diversity of our group. Bill was from a large Catholic family, perhaps considered lower middle class. He went of Yale on an academic scholarship, later getting a business degree from the Wharton School, and then a Ph.D in economics, from NYU. In life, he started out in banking in Paris but wanted to do something more worthwhile (and more ethical), ending up with the Federal Reserve. Haywood grew up in a large, and very poor, share cropping family in North Carolina. He always said they had no money but plenty of love. He credits Peace Corps with exposing him to new possibilities … eventually going on for advanced degrees in Geography and Theology and becoming a successful operative for a national labor union.

As I look at the faces below when we gathered for our first reunion in 2009, I am still in awe of the talent and accomplishments. I don’t know if Peace Corps had some magic in their selection methods or the PC experience itself altered people’s lives. However, the accomplishments of these people (not all are pictured here) are simply amazing. I am so proud of being associated with them.

Here is another group shot (below). It was taken in 2011, in Washington DC where we had our 2nd reunion. There was a 50th reunion of the creation of the Peace Corps and we thought that a good reason to gather. We are dressed up since we are on our way to the Indian Embassy for a fete they have arranged for those of us who served there and were in town. Apparently, we must have left a decent impression on them even though the country program ended in the mid-1970s.

We had just finished an edited collection of stories (written by individual volunteers), which I was able to hand over to the Embassy officials with great fanfare. The top Indian official there that night said something that resonated with us. He believed that the value of the program was not in the technical expertise we brought to their land. No, it was in the sharing and learning about each other that took place. In the end, I think he nailed it.

One last pic before ending. Below is a Google Earth shot of our site. Remember that lonely and bleak desert shot above Today, that same area looks thriving with all kinds of development including a hospital. A wider shot would show green fields and advanced irrigation where merely desert had been. I would like to take credit for all this but humility prevents me (LOL)

This was a cook’s tour of an incredibly complex esperience, one that did change all our lives. If you want more, here is where to go … Our Grand Adventure: The trials and triumphs of India-44!